There’s a line in a self-help book I have that says, “It’s not what happens in life that matters, it’s how you handle it.”

Now that California has passed the “Fair pay to play” act, it’s up to the NCAA to handle it.

How they respond to the new law that will allow student-athletes to accept compensation for the use of their name, likeness or image (NLI) will ultimately decide the future of collegiate sports.

The clock is ticking. Other states are working on similar legislation. It’s even being looked at on a federal level. While the California version isn’t set to begin until 2023, expect other states to try to enact something sooner than that. It’s being fast-tracked. The response can’t wait.

For decades, the NCAA has fought to maintain some level of amateurism within the framework of college athletics. Ideally, we won’t have college sports turn into full-fledged professional minor league sports, especially in football and basketball. That’s not the mission of the governing body.

Remember the commercial about a high percentage of student athletes “turning pro in something other than sports?”

While the new law doesn’t make schools pay athletes – something the NCAA has always been adamant about – it does open the door to every booster, agent and others of “influence” to use the promise of dollars to lure high school recruits to their campus.

Sleazy recruiting practices are pretty much being legalized. Regardless of the intention, there are going to be consequences that the lawmakers didn’t expect to have happen. They’ve made boosters who can offer “endorsement deals” the most prominent recruiters on campus.

Who knows what depths this will sink to?

So, what does the NCAA do now?

The California law prohibits the governing body from “punishing” athletes who accept endorsement payments. They can’t just rule these kids ineligible anymore without breaking the law. Reports are that the NCAA is hard at work with its own proposal and will unveil it sometime this month.

Ironically, the solution is right under their collective noses. The NCAA already has a successful formula in baseball that if implemented in other sports would solve this problem.

In baseball, eligible high schoolers have a choice: commit to MLB’s player-entry draft OR commit to going to college for three years (or when you turn 21) before you can re-enter that draft. This way, it’s the players who are choosing to play for pay immediately in the minor leagues, or go to school and put that pay day off for awhile (like the vast majority of teenage college students do).

In baseball, there are zero claims about student-athletes being “exploited,” which is utter nonsense to begin with because the kids are choosing their own path, knowing full well what’s ahead – go to class OR draw a (somewhat meager) paycheck while they try to work their way to the big leagues.

Professional baseball is a great partner for the NCAA because baseball doesn’t depend on the colleges to be their development system like the NBA and NFL do. With baseball’s (hockey’s too, on a smaller scale) well established farm system, the NCAA has it easy there.

However, there are no actual “farm systems” in place in football or basketball. But there could be.

It’s up to the NCAA to now force that issue with the NFL and NBA.

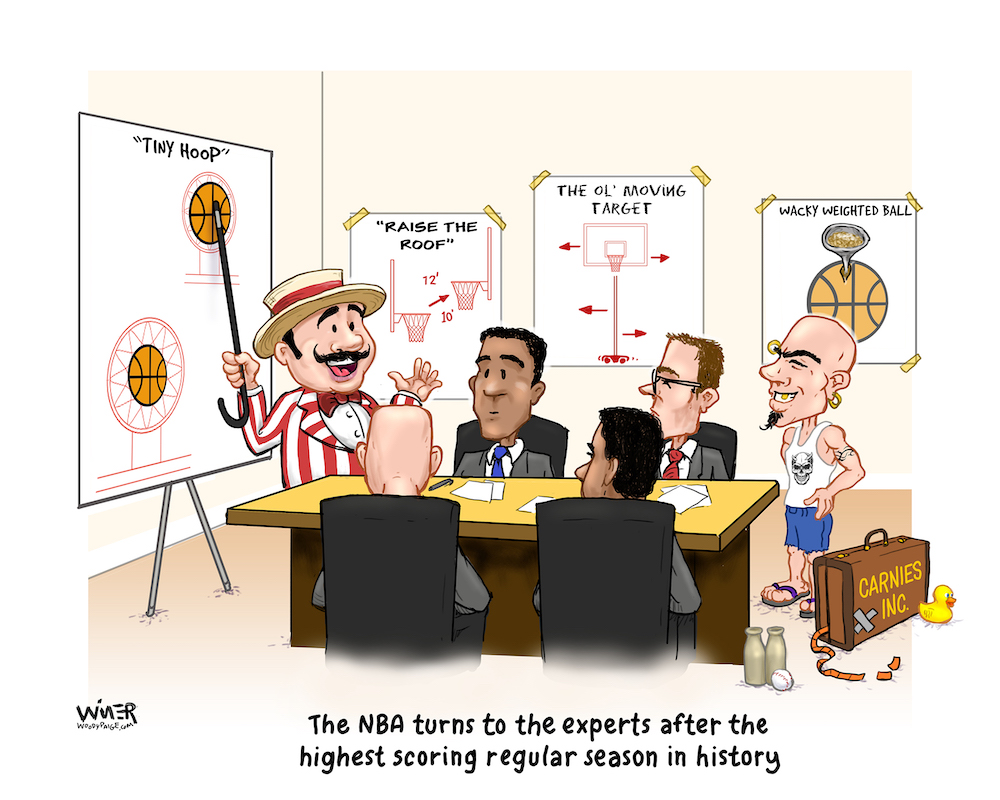

The NBA would be easier. Add three more teams to the NBA developmental league (now sponsored by Gatorade and called the “G-League) and every franchise could have a minor league affiliate. The NBA would need to drop its age requirement for draft eligible players and allow teams to once again draft high school grads and place them in their farm system (no more “one and done” in college hoops).

It would be up to the high schoolers to decide if they wanted to go to a place like Duke for three years, or spend their formative years in the developmental league instead getting that paycheck.

Football wouldn’t be quite so simple, but it could be done.

The NCAA could tell the NFL what they’re being forced to do by the new law, and ask the league to create a developmental program for high schoolers who want to get paid to play immediately.

Knowing there’s a hefty cost involved in starting up a minor league system from scratch, the NFL isn’t likely to simply accept the idea and just go with it. It would take awhile.

But there could be another way.

The startup XFL, which will debut next spring, could be talked into this. Like every other league that has tried to get started, the XFL is looking for a niche — a way to stay relevant after the newness wears off. Becoming a developmental league that gets stocked every year with a new class of five star recruits could be that niche.

High schoolers could declare themselves eligible for the XFL draft out of high school and choose to play for pay immediately, with their eyes still focused on the NFL someday. The XFL would have to accept the idea of their NFL ready players being re-drafted and signed by the big leagues. This would be the perfect solution for young players not yet mature enough for the NFL, but who aren’t interested in attending classes – and there are a boatload of those kids coming out every year.

Whatever comes to pass, the NCAA – if they want collegiate sports to survive – must do something drastic. Their best bet is to force the hand of the professional leagues so that they can be allowed to return to the mission of educating those who want to be students AND athletes.

California has sent an unintended message to the NCAA: Get out of the business of being a minor league for the pros.

There IS a way.

Listen to Mark Knudson on Monday’s at 12:30 with Brady Hull on AM 1310 KFKA and on Saturday mornings on “Klahr and Kompany” on AM 1600 ESPN Denver.