What happened at the Yale-Harvard game Saturday — climate change/fossil fuel protesters storming and occupying the field — almost happened 50 years ago at the landmark “Big Shootout,” the December 6, 1969 matchup of No. 1 Texas and No. 2 Arkansas at Razorback Stadium in Fayetteville.

If the Arkansas band had played the song “Dixie,” the school’s black students and supporters would have, yes, stormed and occupied the field.

In front of the president of the United States.

It could have gotten ugly.

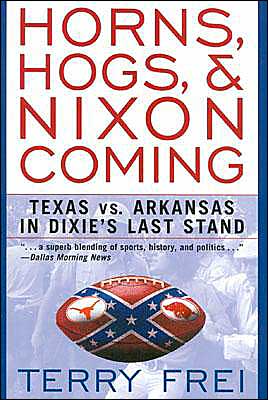

That was one of the subplots I came across, researched and wrote about when placing the classic game in the context of tumultuous times in my 2002 Simon and Schuster book Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming. It’s still in print in paperback editions from two publishers.

Yes, I painstakingly handled the football aspect. It still was the major focus of the book. I told the stories of most of the starters for both teams, that season and that game, a thrilling 15-14 Texas victory.

Both teams had a freshman scholarship player poised to integrate the varsity the next season – running back Jon Richardson for the Razorbacks and linebacker Julius Whittier for the Longhorns – but on that day in Fayetteville, both varsity rosters were all-white.

I even wrote seven pages about one monumental and audacious Longhorns play, “Right 53 Veer Pass,” a deep throw on 4th-and-3 from the Texas 43, from Wishbone Wizard James Street to tight end Randy Peschel. The Longhorns were trailing 14-8 with 4:47 remaining, the play went for 44 yards, and the Longhorns scored two plays later.

But as I documented, there was so much more to it than the game.

That day 50 years ago, former Whittier College scrub Richard Nixon led a delegation of politicians to Fayetteville for the game, and he sat in the stands. Those with him included Arkansas Gov. Winthrop Rockefeller; Arkansas’ two Democratic U.S. Senators, J. William Fulbright and John McClellan; plus young Congressmen (and close friends) John Paul Hammerschmidt of Arkansas and George Bush of Texas.

As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Fulbright was one of the major critics of the Vietnam War and of Nixon. Fulbright also was a former Razorback football star and ex-U of A president who still considered Fayetteville his home. That might have made for both awkwardness and, away from Washington, interesting change-of-pace conversation along the row.

President Richard Nixon and the politicos at the Big Shootout. Bonus points for spotting the future president. He went to Yale, but he probably wouldn’t have protested during a football game.

A cooperative Bush responded in writing to my questions about that day, and after interviewing Hammerschmidt — like Bush a former World War II pilot — on the phone for the book, I later was brought in to join him in his hometown, Harrison, and deliver the annual John Paul Hammerschmidt Lecture at North Arkansas College.

I was honored.

As the Nixon delegation settled in at the game, the U of A’s black students and their sympathizers were poised, listening to see if the Razorback band played “Dixie.”

After the students’ long campaign against the use of the song as the Razorbacks’ unofficial anthem, the Student Senate only a few days earlier in a non-binding vote had recommended that the band drop it from its playlist, and band director Richard Worthington said he would honor that.

Yet nobody was certain that rogue band members wouldn’t play the song, anyway. Plus, a Faculty Senate committee had proposed a ridiculous compromise, suggesting the band play “Dixie” in the first half of the Texas game as a final curtain call, but never again. The song had many defenders on the Arkansas campus and beyond. (The book’s subtitle, Texas vs. Arkansas in Dixie’s Last Stand, had multiple meanings.)

Among the many black Arkansas students I interviewed was Hiram McBeth, from Pine Bluff. This also had been overlooked: With the student group Black Americans for Democracy seeking to integrate as many campus organizations as possible, McBeth raised his hand at a meeting when leaders asked if anyone in the room had played high school football. He tried to point out he didn’t claim to be a star. Yet, McBeth nonetheless was “appointed” to go out for the varsity. In 1969, McBeth was a defensive back on the “B” team, or, essentially, a practice squad player who didn’t suit up for the Big Shootout and was in the stands.

“We had agreed we would head to the field and lie down, all of us,” McBeth, who became a Dallas attorney, told me. “We made sure we were all placed at various places so we could get down there. As soon as the first note was played, we were heading down there and lying on the field, and they were going to have to get all two hundred of us off there. And they were not going to be able to do it in a commercial break.”

Another future president, Rhodes Scholar Bill Clinton, was listening to the game on short-wave radio in London three days after writing his eventually infamous and angst-filled letter about his Selective Service draft status to Arkansas ROTC head Col. Eugene Holmes, a Bataan Death March survivor whose daughter, Linda, was dating and later would marry Razorbacks star tailback Bill Burnett.

I tracked down and talked with a Little Rock attorney, Darrell Brown, who as a law student had suffered a grazing gunshot wound on the inside of his left leg when heading to a BAD strategy meeting the night before the game. He believed the shot came from a passing car and after he made it to the meeting, he was taken to the hospital and stayed overnight. Attending physicians said the shot probably came from a .22-caliber weapon. Tensions were in danger of boiling over.

Dr. Gordon Morgan, an associate sociology professor, was the only black U of A faculty member. After midnight, now only hours before the game, he went to the home of U of A president David W. Mullins and pleaded for Mullins to take a dramatic stance decrying the violence, perhaps appearing on radio or television. Morgan told me that Mullins said he believed the “local authorities” had the situation under control.

After we talked about what happened on the eve of the game, Brown out of nowhere asked me: “Did you know I was the first black Razorback?”

Uh, no, I didn’t.

So Brown, from Horatio, Arkansas, told me about walking on and playing on the freshman team in 1965, with mixed reactions — ranging from supportive to bitterly derisive and ugly — from his teammates and coaches. He saw only brief action as a running back in the five-game season, and then reluctantly decided not to go out for the varsity in 1966.

One more degree of separation: Brown represented former Arkansas Jim Guy Tucker on the defense team in the Whitewater trial and questioned President Bill Clinton in videotaped testimony in the White House in 1996.

Since the song wasn’t played that day in Fayetteville, a “Dixie” protest didn’t become part of “Big Shootout” lore.

I was invited to attend the University of Arkansas’ Black Alumni Reunion in Fayetteville in April 2003 to appear on a symposium panel. There, I heard Judge Wendell L. Griffen of the Arkansas Court of Appeals tell me he was the flagbearer for the ROTC color guard that day and was prepared to throw down the U.S. flag and storm onto the field if “Dixie” was played. Both he and Gerald Jordan, a student journalist in 1969, told me they believed I had underestimated the potential for violence against the black students if they had staged an on-field protest. They also said I hadn’t given Worthington, the band director, enough credit for his courageous stand for making sure “Dixie” wasn’t played. I included Griffen and Jordan’s views in the Afterword updated for Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming’s Taylor Trade paperback edition. (Simon and Schuster’s paperback edition sticks to its original hardback text.)

Another demonstration did come off that day, though.

On the hill above Razorback Stadium, Arkansas physics professor Bud Zinke, a World War II veteran; and U of A student Don Donner, fresh from serving as a combat engineer in Vietnam, were among the leaders of a highly visible anti-war protest.

Donner, who became a Fayetteville attorney, had approached the advance Secret Service delegation bunkered down in a dormitory and was taken to a man he was told was in charge.

Donner introduced himself and asked, “Why the hell can’t I have my demonstration?”

“What?”

“Look, I’ve been in Vietnam and I want to have a demonstration there at the game.”

“Whereabouts?”

“Across the road from the stadium, by the administration building.”

“Hey, as long as you’re not within two hundred feet of the president, we don’t care.”

“But they said you were stopping—”

“We don’t care! As long as you don’t get near the president, we don’t care.”

So the protest came off, in full view of the president and his delegation.

ABC didn’t show it or even refer to it.

It was a different world 50 years ago.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of six other books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his additional non-fiction works are Third Down and a War to Go, plus ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age and March 1939: Before the Madness. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.