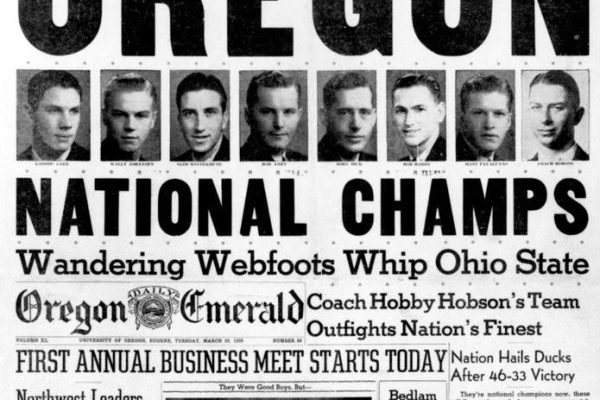

Update, Thursday, March 12: The 2020 NCAA tournament will not be played. I’m going to leave the column that follows as it was when I wrote it Sunday and it was posted Monday. Because of circumstances, it now has become more of a wistful look back to the roots of the tournament without changing a word. May the fun and games return soon. — TF

Welcome to March Madness.

Conference tournaments finish up next weekend. Selection Sunday follows. If you’re typical, you’ll have 27 bracket entries in before the deadlines — and be counting yourself out by the time the field is down to the Sweet 16. But you’ll stick with the NCAA tournament through the Final Four and “One Shining Moment.”

Before the NCAA tournament became a mammoth affair captivating the nation, there had to be an inaugural event that started the sport’s revolution.

The first was in 1939.

The impetus came the year before, when organizers staged a six-team post-season invitational tournament in Madison Square Garden. It was an outgrowth of promoter Ned Irish’s regular-season college doubleheaders at the Garden. His fingerprints were on the invitational tournament, too, but the Metropolitan Basketball Writers Association, made up of New York scribes, founded and sponsored it.

The participants in that 1938 inaugural NIT were Colorado, led by three-sport star Byron “Whizzer” White; plus Oklahoma A&M, Bradley Tech, Temple, New York University, and Long Island University.

Temple routed Colorado 60-36 in the title game.

The New York scribes hyped it as more, but the national attitude seemed to be that the Owls had won a new tournament for New York teams and invited guests, no more suited to select the best team in the land than, say, a holiday tournament.

Two weeks later, the National Basketball Coaches of America gathered at their convention in Chicago. Stanford coach John Bunn brought up the idea of a tournament involving teams from all areas of the country. Bunn was certain his 1938 Stanford team, with star Hank Luisetti, would have won a genuinely open national tournament.

The NABC passed along the proposal for a tournament to the NCAA, then barely 30 years old and with limited resources and power. It wasn’t until October 1938 that the NCAA agreed to sanction the 1939 tournament. The catch: The NCAA stipulated that the NABC would assume all the financial risk.

Ohio State coach Harold Olsen was named chairman of both the tournament and selection committees. On December 14, 1938 in Columbus, Olsen announced the 1939 tournament framework. Notably, the Associated Press story began: “The National Collegiate Athletic Association’s plan to select America’s undisputed college basketball champion advanced a step today . . . “

Olsen announced plans for two four-team “sectionals,” one for teams east of the Mississippi River and one for teams west of it. The sites still were up in the air. Also, Olsen said one team from each of eight districts would be in the tournament. He indicated it was preferable if each district selection committee could simply pick a team as its representative in the eight-team national field, but said each district also could hold qualifying playoffs.

Eventually, the four-team Western championships were scheduled for San Francisco’s Treasure Island, in conjunction with the Golden Gate International Exposition, the 1939-40 world’s fair. The Eastern regional was set for the Palestra in Philadelphia in March 17-18.

The two regional winners would meet in the NCAA’s national championship game on March 27 at Northwestern’s Patten Gymnasium in conjunction with the NABC convention in Chicago.

So how’d it play out?

It’s true that a handful of prominent programs, including SEC champion Kentucky, Big 7 champion Colorado and Big Six co-champ Missouri turned down NCAA bids. The Buffs passed on filling the Rocky Mountain district spot in the West regional. League runner-up Utah State went instead. Big Six co-champion Missouri declined to participate in a mini-tournament in Oklahoma City to determine the District 5 bid.

The pertinent point here is that those programs didn’t spurn the NCAA tournament to accept an NIT bid. They just stayed home.

The eight-team field and regional semifinal matchups ended up this way:

East in Philadelphia:

— Big Ten champ Ohio State vs. Southern Conference champ Wake Forest.

— Independents Villanova vs. Brown.

West in San Francisco:

— Pacific Coast Conference champ Oregon vs. Southwest Conference winner Texas.

— Oklahoma (winner of the three-team District 5 play-in) vs. Utah State.

The Howard Hobson-coached Oregon Webfoots — with a starting five of Pacific Northwest small-town boys — cruised to the title playing what then was considered a racehorse style in the second season since abandoning a jump ball after every basket. They beat Texas (56-41) and Oklahoma (55-37) in San Francisco, then from there took the long train trip to Chicago and defeated Ohio State (46-33) in Evanston.

(A piece of trivia: The leading scorer in the first-ever NCAA title game was Oregon junior forward John Dick, with 13 points. This isn’t trivial: He was the U of O’s student body president the next year, a Naval flyer during World War II and the Korean War, the captain of the USS Saratoga supercarrier during the Vietnam War, and eventually a rear admiral.)

The Webfoots finished 29-5 overall. They went 6-2 on a December barnstorming swing through the east and midwest that included losses to CCNY in the Garden and at Bradley Tech in Peoria. Especially considering their three double-digit routs in the tournament in a relatively low-scoring era, they were the best team in the nation by the end of the season.

Regardless, it’s not the Webfoots’ fault that other programs passed on the chance to be memorialized as the first NCAA champions. They went and they won. (Still officially the Webfoots at the time, a nickname that honored fishermen, not fowls, they also increasingly were being called the Ducks.)

And what of the competing NIT?

The Clair Bee-coached Long Island Blackbirds beat New Mexico A&M, Bradley Tech and Loyola (Chicago) to win the NIT and finished 24-0. Yes, many cited the Blackbirds as the nation’s best team, but some of that was because the New York scribes had axes to grind with their own tournament. Both then and since, those touting the 1939 NIT champions as better than the 1939 NCAA champions often disregarded the Blackbirds’ bizarre schedule.

They had had a handful of quality wins in the Madison Square Garden doubleheaders, including against Kentucky, USC and Marquette. But the LIU case was undercut because the Blackbirds had only one — one! — legitimate road game all season, against La Salle in Philadelphia. In addition to their eight total wins in the Garden, the Blackbirds were 15-0 in their tiny home gym at the Brooklyn College of Pharmacy. There, they beat up on the likes of the Princeton Seminary, Stroudsburg Teachers and the John Marshall College of Law.

That doesn’t mean the Blackbirds were frauds; it means they weren’t genuinely tested with a conventional schedule with something close to half the games on the road — the sort of tests the NCAA tournament teams from major conferences routinely faced.

To be fair, four of the 1939 NIT entrants — LIU, Bradley Tech, Loyola and St. John’s — would have been genuine threats if they had ended up in an eight-team or expanded NCAA tournament. But the NIT’s six-team field also included Roanoke College, so it’s ludicrous to proclaim the NIT as better and deeper that year.

What we do know is that the coaches’ association, the NABC, determined it had lost $2,531 on the first NCAA tournament.

The NCAA agreed to pay that off.

In exchange, the coaches turned over the tournament completely to the NCAA.

It was a better deal than $24 for Manhattan.

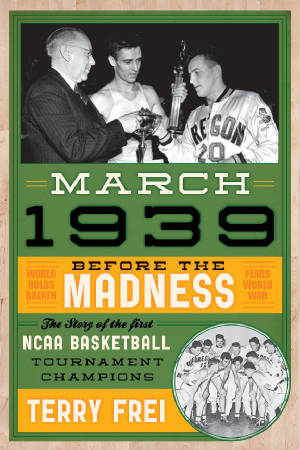

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of March 1939: Before the Madness, on which this column is based. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and also among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming and Third Down and a War to Go. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.

More from The Woody Paige Sports Network:

- Projected salary cap space for all 32 NFL teams heading into the offseason

- Chris Harris Jr. drawing interest from multiple NFL teams

- Betting Odds For Where Philip Rivers Will Play In 2020

- NCAA asked to host March Madness tournament without an audience

- Betting odds to win the 2020 college basketball national championship