Deb Ploetz settled with the NCAA last year.

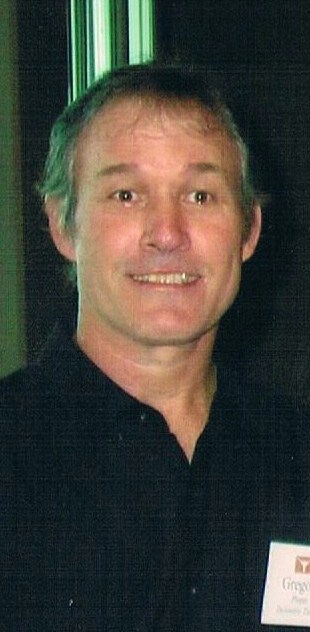

The widow of former Texas defensive tackle Greg Ploetz still hasn’t made her peace with football, though.

And I don’t think she ever will.

Ploetz vs. NCAA, the first Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy-related lawsuit against the NCAA, schools or leagues to go to trial, was settled during the third day of testimony in Dallas last year. Deb, Greg’s wife of 37 years at his 2015 death at age 66, was the lawsuit’s individual plaintiff, along with Greg’s estate.

A 5-10, 205-pound behemoth when with the Longhorns, and leaner than that later in life, Greg suffered from dementia in his final years and an examination of his donated brain after his death found that he had Stage 4 CTE – as bad as it gets.

As the 50th anniversary season of the Longhorns’ 1969 national championship team – a team Greg played for and I wrote about in my 2002 book Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming – is about to begin, I caught up with Deb on Wednesday. The book still is in print in paperback editions from two different publishers, and the anniversary season will bring renewed attention to the ’69 Longhorns and Razorbacks.

Greg’s deterioration and death will be one of the sad subplots.

I interviewed Greg in 2001 and extensively profiled him in the book, then met Deb when she joined Greg at the 2004 joint reunion of the ’69 Longhorns and Razorbacks in Fayetteville, where I was the (neutral) keynote speaker. An art teacher and artist, Greg began mentally deteriorating the next year, and eventually dementia took hold.

I saw them both in the Denver area when Deb brought the very ill Greg to Colorado to be able to openly use marijuana products to ease his pain and calm him. And I stayed in touch with Deb after they left Colorado, both before Greg’s death and after.

On Wednesday, Deb said she had heard of the furor over Andrew Luck’s retirement at age 29 and essentially wondered out loud, as she does for anyone walking away from the sport: Good for you … and what took you so long?

She said she had some regrets about accepting the lawsuit settlement from the NCAA, which all but ruled out a verdict becoming a major precedent moving forward. But continuing the case through verdict and appeals would have added to trauma in her personal life and stressful for her family, and she still believed she made her point.

“When we went to lobby and we met with senators and whoever, and talked to their staff, they said the only way to make a difference was to file a lawsuit,” Deb told me from Dallas. “I felt like I helped make people aware of the risk of playing tackle football. Now Greg has opened a door for so many (ex-players) that are ill, whether it’s ALS or Parkinson’s or CTE. Greg’s lawsuit, other people will reference it when they file a lawsuit.

“I feel good that it opened the doors for so many people because the NCAA had to give over so many important documents they were withholding from so many other people. Greg’s case was so strong, that’s why it went to trial. There was no way to deny that he died from CTE.”

She said that her lawsuit and crusade against football has had its toll.

“I’ve lost friends and family (support) because of my belief that football caused my husband’s CTE,” she said.

Some of Greg’s Longhorn teammates were prepared to testify for the NCAA.

As part of her anti-football efforts, Deb contributed an eloquent chapter on Greg for the book Brain Damaged: Two-Minute Warning for Parents, released earlier this year.

Former NHL winger Daniel Carcillo wrote the foreword and family members told the stories of brain-injury victims in separate passages. Other co-authors include Mary Seau, sister of Junior Seau, the former Chargers, Dolphins and Patriots linebacker who committed suicide. Other listed co-authors are Kimberly Archie, Jo Cornell, Tiffani Bright, Solomon Brannan, Debbie Pyka, Cyndy Feasel, Kira Hoffman, Michele and Michael Grange, Marcia Jenkins, Kim Jenkins, Nikki Langston, Leanne Pozzobon, Keana McMahon and Darren Hamblin.

Deb also wrote a shorter tribute to Greg on the Boston University-based Concussion Legacy Foundation’s web site. It begins:

Gregory Paul Ploetz was a Renaissance Man. He was brilliant, clever, and could do most anything. He was not only a gifted teacher and artist, an educated speaker, but he could also change the oil in his car and plumb and wire an entire house.

In advance of the trial, the NCAA subpoenaed and deposed me, and I turned over a tape of my book interview with Ploetz with a clean conscience because the material about Greg in the book is a virtual transcript of what’s on the tape. There were no surprises. And I wasn’t even sure which side in the suit the tape would have aided more.

On the tape, Ploetz talks about how he initially was listed as the freshman team’s fifth-team defensive end.

“I thought, ‘God, I’m going to have to kill somebody,'” he told me. He said he took advantage of an “eye opener” drill, where a tackler went one-on-one with a runner picking a hole between bags. He blasted the ball carrier. “They picked him up, and I got up and somebody asked me, ‘Now what’s your name again?'” Ploetz recalled. “The next day, my little ring is hung at starting linebacker.”

As a sophomore for the varsity, he played linebacker, then switched to defensive tackle in that monumental 1969 season. He eventually was named UT’s top art student as a senior in 1971.

In the art department, Ploetz looked as out of place as a Haight-Ashbury refugee on the Jester Center dormitory’s football floors. “I was pretty sympathetic with the antiwar movement, but I was required to wear my hair short and I never participated in any rallies or walks,” he said. “I had lots of friends who did in the art department. It was kind of a joke over there. I only weighed about 205, but I was pretty bulked up. With short hair, I’d go into a painting class and people would look at me and say, ‘Who’s that?'”

His teammates followed his work.

“As I took the life drawing classes, we had nudes, of course,” he told me. “The guys would literally be waiting at the dorm: ‘Here he comes! Let’s take a look!’ … They’d get my pad out and look at the girls I was drawing.”

Ploetz had a good game against Arkansas, helping keep pressure on Razorbacks quarterback Bill Montgomery.

He didn’t play in 1970.

He married a girl from back home in Sherman, Texas, and she gave birth to a son, Chris.

Chris was very premature and Ploetz called on the priest connected to the football team, Father Fred Bomar, to come to the hospital to immediately baptize the baby. Chris’ godfather at the ceremony was Freddie Steinmark, the Longhorns’ defensive back from Wheat Ridge, Colorado, whose cancer-riddled leg had been amputated six days after he played in the Arkansas game. Chris survived. Freddie died in 1971.

(Because I also attended Wheat Ridge and was one of Freddie’s successors as a Farmers’ baseball captain, I was steeped in Steinmark’s courageous story when I was in high school. That was part of the reason for my original interest in the Texas-Arkansas game, which I first wrote about at the 25th anniversary in December 1994 for The Sporting News. Longhorns starting guard Bobby Mitchell also was from Wheat Ridge High.)

Ploetz also earned a master’s in fine arts and taught at several schools, including Arkansas-Little Rock, and was divorced before buying, fixing up and selling houses. He and Deb were married in 1978. He missed teaching, though, and settled in on the faculty at Trimble Tech High School in Fort Worth.

After he became ill, and during his stay in Colorado, Deb told me that when she drove by kids playing football, she wanted to pull over, get out of the car and lecture parents.

“I wanted so bad to go tell them, ‘Do not let your son play football,'” Deb said.

While coping with Greg’s illness, she originally told me she wasn’t planning to sue, but she changed her mind. She said that seeing Greg struggle and suffer led to her decision.

As filed, the suit charged the NCAA with a “failure to take effective action” to protect Ploetz” from the long-term effects of concussions and sub-concussive blows to the head” he suffered while he played for the Longhorns in 1968, 1969 and 1971.

It said the NCAA “failed to educate its football-playing athletes, like Gregory Ploetz, on the long-term, life-altering risks and consequences of head trauma in football.” It charged the NCAA “failed to address and/or correct the coaching of tackling or playing methodologies that cause head injuries” and didn’t educate coaches, trainers and schools about concussion symptoms. And it argued that the NCAA “failed to implement system-wide ‘return to play’ guidelines.”

A former Ploetz teammate and friend, attorney Julius Whittier, the Longhorns’ first African-American football letterman, in October 2014 was suffering from early onset Alzheimer’s. He also was a major figure in Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming. He was on the freshman team in 1969, so he didn’t play in the landmark game, but was in the program. I interviewed him in his Dallas office and also told his story. On his behalf, his sister, Mildred filed a $50-million class action lawsuit against the NCAA on behalf of players who did not make the NFL but were suffering from brain injuries. He died in September 2018. He was 68.

I have mixed feelings about this. It was 50 years ago. Making blind assumptions that football and concussion issues led to the former players’ brain maladies — whether dementia or, more specifically, Alzheimer’s — can be a slippery slope, at least before post-death CTE diagnosis comes into play.

The football concussion “protocol” once was observation. Too often the assessment was that you got your bell rung and, if possible, you went back in. The players thought that way, too. We’re so much smarter and aware now. And not just in football. Similar reassessments have taken place in most sports, including hockey and even soccer. Apportioning blame with 20-20 hindsight now, both in this and the $1 billion class-action settlement between the NFL and former players, can lead to oversimplification.

In fact, my father, Jerry, was the head coach at Oregon in 1969, and some sloppy work by a law firm filing a lawsuit on behalf of a former marginal Ducks player led to my father being connected to it in original media reports – before it came out that the firm had the years involved fouled up and players mentioned as the plaintiff’s teammates had no idea who he was.

Austin Meek, then of the Eugene Register-Guard, eloquently corrected the record in a column quoting several of my father’s players noting how progressive he was on the concussion issue. His own career ended during his senior year at Wisconsin, and the Wisconsin State Journal story said his problems were caused by “an acute sinus condition.”

In those days, that was one of the codes for “concussions.”

Rather, he had had suffered repeated concussions for years, leading to headaches. I’m assuming if he mentioned that to military doctors, it might have prevented him from flying 67 missions in a P-38 fighter in the four-year gap between his sophomore and junior seasons.

But the story noted the Badgers’ starting guard “was advised to give up the sport after limited work last week and this brought on discomfort. Possessed of tremendous competitive spark, Frei is certain to be missed. Giving up football was hard to take, but Jerry realized that it was the only thing to do.”

So I’m leery about careless retroactive application of modern standards, citing such things as relentless hitting in practices and perceptions of “toughness.” I’m leery because … well, that’s just the way it was.

“It was a different time,” Deb said. “But I felt the NCAA, not UT, they had the responsibility to tell what they knew and they did not.”

The 2018 settlement prevented the Ploetz case from becoming a major precedent.

But it made its point.

“I wish people would open their eyes and their hearts and realize football is not the only way to build your self-esteem, your confidence,” she said. “You can play other team sports and still feel complete and be a part of your community.”

Deb was speaking from football-crazy Texas, of course. Nationally, though, the numbers are down — but not down as much as I would have predicted a decade ago.

The National Federation of High School Associations says the peak in particpation for 11-man teams was a in 2009-10, and that it has dropped about 6.5 percent since, but the number of players still is over one million nationally. The other significant possibility is that we haven’t seen the effects of the doubt over the safety of the game show up in participation levels at the high school level, and that could take place as those declining to play — or not being allowed to play — youth football get older.

But for now, football is hanging in there.

Deb said she is encouraged that the emphasis now is on delaying participation in tackle football until age 14, and she’s aware of all the heightened standards for spotting head injuries and for protocol.“People are listening,” she said. “One of my friends, their grandchildren play football. They had me speak at their church. They are adamant that their grandchildren quit playing. The new research says don’t play until 14, but I don’t know. People like me don’t want you to play at all.”

Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming, and Third Down and a War to Go, plus ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com.