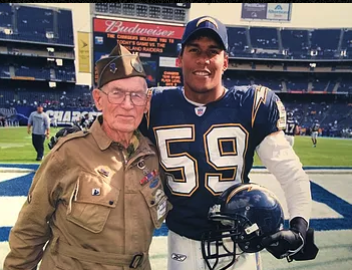

For 13 seasons in the NFL, San Diego native and former UCLA Bruin Donnie Edwards was a linebacker with the Chiefs and Chargers.

Ten years after his early 2009 retirement, his new focus is his remarkable donation-supported organization, the Best Defense Foundation, which escorts U.S. World War II veterans — free of charge — back to the sites of their combat service.

This year, mostly at 75th anniversary benchmarks, the foundation has taken veterans to sites of Pacific island battles; to Normandy and Omaha Beach; and to The Netherlands.

Edwards, 46, is founder and executive director of the foundation based in Solana Beach, California. He went on many USO Tours to visit U.S. bases as a player, and still does that; and also was involved in taking veterans on return trips for 12 years before officially incorporating the foundation as a non-profit corporation last year.

Edwards also drew attention when he appeared with his wife, Kathryn Edwards, on the sixth season of the reality series, “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” in 2015-16.

But the Best Defense Foundation is his passion.

Edwards credits his Apache Nation grandfather, Maximo Razo, with drawing him to the cause of World War II veterans. Razo was an Army sergeant stationed at Schofield Barracks on Oahu, next to Wheeler Airfield, at the time of the December 7, 1941 attacks. As the war continued, Razo also served in the Philippines and on Okinawa.

“Growing up in San Diego, it’s a big military town,” Edwards told me Sunday from Amsterdam, on a separate business trip. “My grandfather was there in my life as my father figure. He was very, very proud of his service. As a young kid, I used to go everywhere with him, even going to the VFW and hanging out with all his brothers, playing darts and shooting pool.

“Before he passed away, he was always telling me, ‘Don’t forget what we did in the war. We gave you the opportunity. It doesn’t matter where you come from, Donnie, if you work hard, you can achieve it and make it happen.’”

Edwards said the seeds for the trips came in conversations with veterans in the early 2000s.

“They were talking about going back to Normandy,” Edwards said. “I said, ‘Really? You want to go back?’ They said, ‘Absolutely.’ I said they should do it. They’d say, ‘I can’t go back. I’m on Social Security, I don’t have any money.’ I thought to myself, ‘Well, I’ll take you.’ That’s kind of how it started.”

In addition to the battlefield return program, the foundation also has Operation Archive, recording veterans’ memories of their service.

“We have to record them for perpetuity, so we never forget,” Edwards said. “And as long as our veterans are healthy enough and want to go back to the World War II sites, I’m going to provide them that opportunity.”

The latest Best Defense Foundation program was the 10-day trip to The Netherlands, where Edwards and other escorted nine veterans.

They first were among the veterans from many nations saluted in the southern part of the country, in the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the nation’s liberation from German occupation.

Next, they moved north to Nijmegen to salute Operation Market Garden, which took place from September 17-25, 1944.

They also spent one day at Bastogne, in late 1944 the site of part of the Battle of the Bulge.

(An NFL Films crew also made the trip and put together this moving feature.)

“The parade in Maastricht a couple of weeks ago for the liberation of The Netherlands was by far the most amazing parade I’ve been a part of with veterans,” Edwards said. “There were probably 75,000 to 100,000 people out there, to be there for the veterans. They were 10 deep, clapping and coming up and saying thank you with flowers.

“One of our guys, Francis Turner, is 100 and a half years old. He said, ‘Look at all these people, Donnie.’ I said, ‘Mr. Turner, these people are here for you, saying thank you. You’re not only representing yourself, but all your brothers that are no longer here.’”

Earlier, in June, Edwards and the foundation took 14 other veterans to Normandy to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day. They participated in ceremonies on Omaha Beach and made other appearances in Normandy, plus a side trip to Paris.

That came after Edwards and his organization escorted another group of surviving veterans to Iwo Jima, Saipan, Tinian and Guam, the sites of fighting against the forces of Japan in the Pacific Theater. The Battle of Iwo Jima, fought from Feb. 19-March 26, 1945, is the best known.

“Talk about memories and closing the circle,” Edwards said. “It’s a chance to connect, with the camaraderie and the brotherhood. We want to give them chances to go back and participate in the commemorations and ceremonies, see the parades and see the love. It’s an honor they deserve and should definitely get.”

Edwards said he already has taken one group of veterans back to Vietnam, but moving on to the Korean War, and Vietnam is on the back burner.

So who has Edwards, his foundation and its volunteers touched?

The list is long, of course, but on Friday, I also again touched base with Leila Morrison, the only woman veteran who has been on a Best Defense Foundation program. Now 97, she lives in Windsor, Colorado, between Greeley and Fort Collins.

As a combat nurse, she came ashore at Omaha Beach after the troop landings and followed the combat lines across Europe, working under trying conditions in operating “rooms” that actually were triage tents.

With the 118th Evacuation Hospital, Morrison witnessed both the carnage of war and, at the Buchenwald concentration camp, the results of the horrific actions of Nazi Germany in implementing the unspeakable “Final Solution.”

To her, Donnie Edwards is not a former NFL player.

To her, Donnie Edwards is a hero.

“Oh, I thought he was wonderful,” Morrison said. “I thought his wife was just as nice as he was. They’re a very unusual couple and have a real feeling for veterans, especially veterans that were there before VE Day.”

On June 6, the 75th anniversary of D-Day, thanks to the Best Defense Foundation, Morrison looked out over Omaha Beach.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” Morrison told me. “It was so different from 75 years ago, when we arrived. There wasn’t anything recognizable except maybe the sand on the beach.”

Morrison and the Best Defense Foundation group sat behind President Donald Trump at the official 75th anniversary commemoration ceremony. Trump introduced and hugged one member of the party, Russell Pickett, who as a 19-year-old private in the 29th Infantry Division was among the first to arrive on shore, braving the German fire. As Morrison watched, French president Emmanuel Macron helped Pickett stand.

“They told us while we were there that we were probably the last World War II folks who would be there for a public ceremony, and it really was a big one,” Morrison said.

The commemoration ceremony was the highlight of a 10-day program.

“It was quite a trip, especially for an old woman,” Morrison told me. “We were treated like royalty. Even though it’s three generations later, the people seemed to really be willing to remember it and they’re teaching their children about what happened. We went to a couple of schools and the children really welcomed us and had made little banners. They seemed to know and understand quite a bit about World War II.”

She met the group in Los Angeles and they flew — in First Class, thanks to upgrades from United Airlines — to Paris and eventually ended up in Normandy.

Activists who support Edwards include Jake Schroeder, who is the head of Denver’s Police Activities League and sings the National Anthem at Avalanche games; and Avalanche television broadcaster Marc Moser. They have become close friends of Ralph Peeters, the Best Defense Foundation’s Netherlands-based program director.

Both Moser and Schroeder were at Normandy for the 75th anniversary with their daughters and interacted with Morrison.

Morrison became beloved among Best Defense Foundation personnel, all devoted volunteers, and charmed the young people meeting the American visitors.

“She was an inspiration and a lovely lady to have on the program,” Peeters told me. “She was an ambassador for all nurses who served in World War II.”

Raised in Blue Ridge, Georgia, Morrison entered the Army Air Corps as a nurse after her graduation from nursing school in 1943. After training, she was shifted to the Army and soon was commissioned as an officer. Also while at Camp Bowie in Texas, she met a dashing Army officer named Walter Morrison at a dance and turned down his virtually immediate marriage proposal, saying she couldn’t get married while a war was raging. But they remained in touch.

She was transported to Scotland on the converted Queen Elizabeth, and briefly was stationed in England before she was assigned to the 118th Evacuation Hospital. Then she and other nurses traveled on a British ship, the Southampton, to Omaha Beach.

Morrison said it was “a couple of months” after the D-Day landings. The battle lines had moved on, but the goal was for the medical personnel in the unit, including 40 doctors and 40 nurses, to catch up.

“We could not come in very close, because of the mines and sunken ships still there in the harbor,” she said. “So we had to swing off this little, bitty ship on this rope ladder. Some GIs were there in this little LST (Landing Ship, Tank) boat. It opens up in the front. We went in on that, and we walked out of it onto the beach. There was a two-and-a-half-ton truck there, and that’s what we toured Europe in, all the rest of the time. They took us down to a small town there in Normandy and then we proceeded on to where the lines were to set up our hospital.”

They moved through France, Luxembourg, Germany and Czechoslovakia. “It was all in tents,” she said. “We lived in tents. The hospital was in tents. It was all a bunch of tents with a big red cross on top.”

The unit treated the seriously wounded, hoping to get them alive to better facilities, usually station hospitals.

“We only took emergencies,” she told me. “If we thought a soldier would not make it back to a station or a general hospital, we took them and brought them out of shock and stopped their hemorrhaging for surgery.”

When I asked her about following the battle lines, she responded: “It was a complete blackout, of course, and we traveled a lot at night. We’d say, ‘Where are we?’ And most of us would say, ‘Well, I don’t know. Somewhere in Germany or somewhere in France.'”

When they arrived at Weimar, Germany, the Buchenwald concentration camp there had just been liberated.

“We pulled into the town and set up our tents and we were told that we would be moving on the next day,” she said. “Then they told us that evening, ‘Buchenwald is just across the street here, you could walk over there,’ They said, ‘You girls be ready in the morning because we’re going to have to go down there and help out.’ The next morning, we were ready to go and they came and said, ‘You girls can’t go today. The doctors are already down there and the conditions are too deplorable for you girls. You have to wait until tomorrow.’ So that’s what we did.

“The next day we went down and they had it cleaned up — I guess that’s what you would call it — to a certain extent, and we saw things that I still have a hard time believing. The poor people.”

They saw the crematorium, stacks of bodies and emaciated survivors.

“The crematorium, they had it worked out like a factory of murder,” she said. “It was a two-story place and they had eight ovens on each side of this brick crematorium.”

After Germany’s surrender and after returning to the U.S., Morrison was told she would be deployed in the upcoming invasion of Japan. But that nation surrendered in August 1945.

The storybook wartime romance had a happy ending. Leila married Morrison, who served in George Patton’s U.S. Third Army. Leila was a civilian nurse for 30 years, and after Walter’s death, she came to Colorado from Georgia to be near her son, Wally, and his family.

For many years, Morrison said, she didn’t talk much about her wartime experiences with anyone but her husband.

“The two of us could talk about it and understand,” she said. “But just didn’t talk to other people about it,” she said. “I hear people say, ‘Oh, my grandpa served, but he wouldn’t talk about it.’ We didn’t either, for years. We had two daughters and a son and my daughter asked years later, ‘Well, Mom, why didn’t you tell us some of it? You never mentioned it to us.’ It was all such a horrible thing and my husband and I could talk to each other. He understood. We had an outlet for the two of us because we could share it.”

The past 17 months have been dizzying for Morrison.

She was one of 123 veterans who were part of the Honor Flight Northern Colorado trip to Washington D.C. in May 2018. This year, in a February ceremony at her retirement home in Windsor, she was one of six World War II veterans with Colorado connections who received the French Legion of Honor Medal from French consulate general Christophe Lemoine for their service in Europe. That ceremony came about because of the tireless efforts of Northern Colorado veterans advocate Brad Hoopes, the publisher of Remember and Honor.

Hearing of her story, Edwards and the Best Defense Foundation reached out to her and made her part of the contingent to France.

In Normandy, the group also visited cemeteries and laid wreaths. But it all came back to Omaha Beach, the focal point of the trip.

“When we first pulled up, I looked out there at that big ocean,” Morrison said. “It was a cloudy day. The wind was blowing. I thought, ‘Oh, my goodness, how in the world did I ever have nerve enough to swing off the side of that ship?’ I just couldn’t believe I had done that. Of course, 22 years old and 97 years old makes a little bit of a difference there.”

Donnie Edwards, his foundation, contributors and volunteer supporters who aid the program’s veterans – all helped make the returns to the sites of their service possible for Morrison and others.

“You can see my passion,” he said with a laugh Sunday as our conversation wound down. “I put my action where my mouth is. I truly believe that. I’m so blessed and honored to be an American. Things like this don’t happen unless you’re born in the greatest country in the world, and that’s America. It’s on the backs of the men and women that served. I don’t forget that.”

Snap off a salute to all of them.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming, Third Down and a War to Go, and ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.