On the field during overtime Saturday, as Nebraska was setting up to attempt the potentially game-tying field goal at the other end, I moved to a position behind the north end zone in Boulder’s red-drenched Folsom Field.

Still facing the field, I heard a yell. I assumed I was blocking someone’s sight. So I took a step back and then felt a hand on my shoulder. I turned.

There, at the rail of the camera box, was long-time family friend Daniel Graham, CU’s 2001 John Mackey Award winner as the nation’s top tight who later had a 10-season career with the Patriots, Broncos and Titans.

We warmly shook hands and spoke briefly.

Then I turned back to the field and watched Isaac Armstrong’s 48-yard attempt sail wide right.

Daniel opened the gate and charged past me, joining the storming of the field and the celebration. Within seconds, the field was a sea of black and gold and Nebraska fans began plotting their returns, whether to the Denver area or Ogallala, Cozad, North Platte, Lincoln and Omaha. (In a piece on my web site, I opined that there should be a way to wedge additional NU-CU rivalry games into altered future schedules and make Denver the Jacksonville of Georgia-Florida and the Dallas of Oklahoma-Texas.)

Colorado, down 17-0 and written off at halftime, had won 34-31, thanks to an amazing comeback engineered by senior quarterback Steven Montez, who threw for 375 yards and two touchdowns.

It was one of the two marquee college games decided in overtime Saturday, joining Michigan’s earlier 24-21 survival against Army. The Black Knights and Wolverines traded touchdowns in possessions starting at the opposing 25 before Michigan added a field goal and then recovered an Army fumble to end it.

Then, on Sunday, the Chargers beat the Colts 30-24, getting Austin Ekeler’s 7-yard run to conclude an 8-play, 75-yard drive on the opening – and only – possession of overtime. Later, the Lions and Cardinals tied 27-27 when each team notched a field goal in overtime, and they still were tied at the end of the 10-minute period.

This is not going to be a current OT rules primer.

I’m going to say what they should be.

For both college and the NFL.

Use the existing college system as the model – yes, including for the NFL — but massage it.

Use it for both the regular season and postseason.

For the NFL, this starts with the principle I espoused for many years while covering the NHL as a (very) young writer, including chronicling the struggles of a team that finished with 21 ties in an 80-game season. Twenty-one.

Consumers, especially those who bought tickets and are on the scene, deserve a definitive outcome – a winner and a loser – for their investment, whether of money or emotion.

A tie shouldn’t be possible. Not even if it’s an NFL rarity. There were two in 2018 – Steelers 21, Browns 21; and Vikings 29, Packers 29 – before the Sunday tie in Glendale.

Plus, and I realize this is jumping on the pile, it should be impossible to lose without having a possession in overtime. That’s whether it’s the Chiefs in the AFC championship game after the 2018 season, or the Colts on Sunday.

Here’s my proposal:

- In overtime, both teams gets a possession starting at the 50. That assures each team has to get a first down before settling for a field-goal attempt.

- If neither team scores on that first possession, or both get matching field goals or touchdowns, they move in.

- Each team gets a second possession, starting from the opposing 30.

- If the score still is tied after those second possessions, the matching third possessions start at the 10.

- And if – as is extremely unlikely – it gets that far and they’re still tied after that, subsequent matching possessions all start at the 10.

That’s it.

It isn’t that complicated.

No ties.

We’d finally have a system that makes sense.

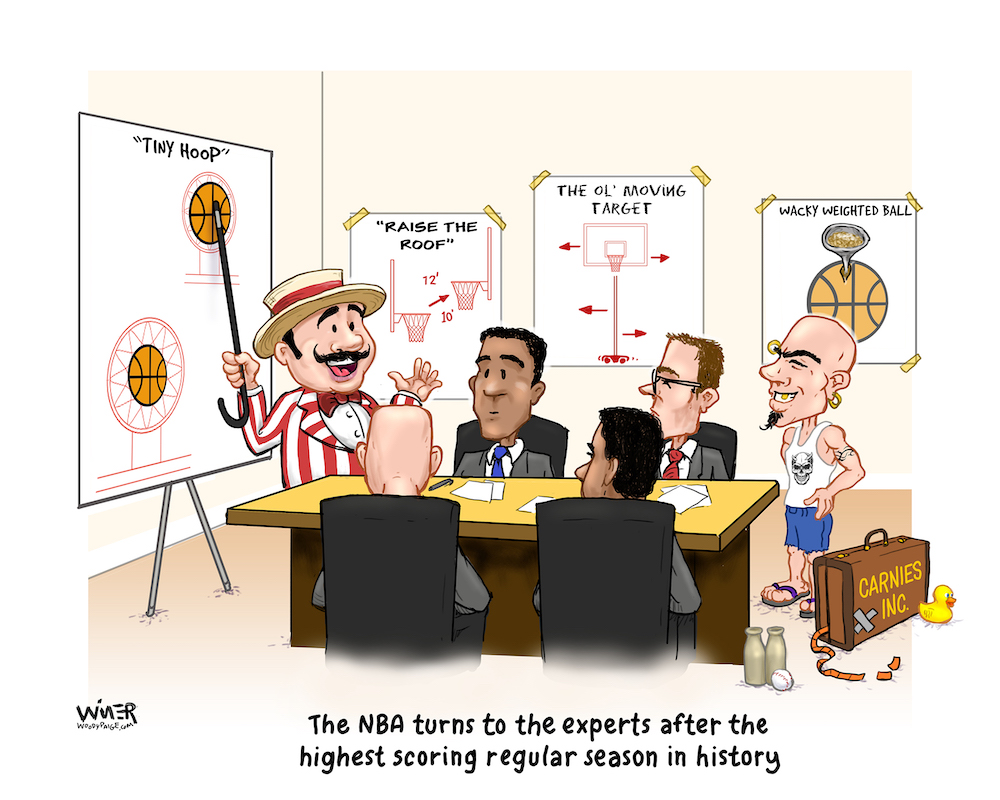

In the NBA and MLB, the “overtime” standards are obvious and traditional.

The only way I’d tweak the NBA system – five-minute overtimes – is to additionally reduce the number of OT timeouts. Those were cut from three to two (plus a 20-second timeout) for the 2018-19 season. The flood of timeouts in the final minutes, and then the OT, is the league’s biggest plague. I’d go for no timeouts at all in the final two minutes of the fourth quarter and OT. Let the players play and decide it rather than have commentators praising the coaches for the intellectual equivalent of splitting the atom for calling an “obvious” timeout.

The NHL finally “got it,” thanks to Ken Holland, then the GM of the Detroit Red Wings and now in the same position with the Edmonton Oilers. After some evolution, the system of 3-on-3 and then, if necessary, the penalty-shot shootout, is brilliant. You watch the 3-on-3, with ice suddenly seemingly becoming a frozen Lake Ontario, and you’re tempted to wonder why they can’t do this all the time. A scoreless five-minute, 3-on-3 overtime can be thrilling, mainly because it almost always requires both goaltenders to be heroic.

And for all the denigration of penalty shots as being like breaking ties in basketball with a free-throw shooting contest, that ignores that it at least involves skills and moves that resemble what can happen in the “normal” parts of games. The problem is that in order to gain approval for a somewhat revolutionary concept, the NHL guaranteed each team a point in games that go to OT or a shootout, meaning some games are worth three points and some two. It also produces standings that allow coaches of teams that are 22-22-8 (the 8 represents overtime and shootout losses) to claim they’re playing “.500 hockey,” and in general create illusions that teams are doing better than they really are.

If the NHL could just make all games worth three points, awarding three to winners in regulation, the hockey system would be perfect.

The NFL, on the other hand, has a long way to go.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming, and Third Down and a War to Go, plus ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com.