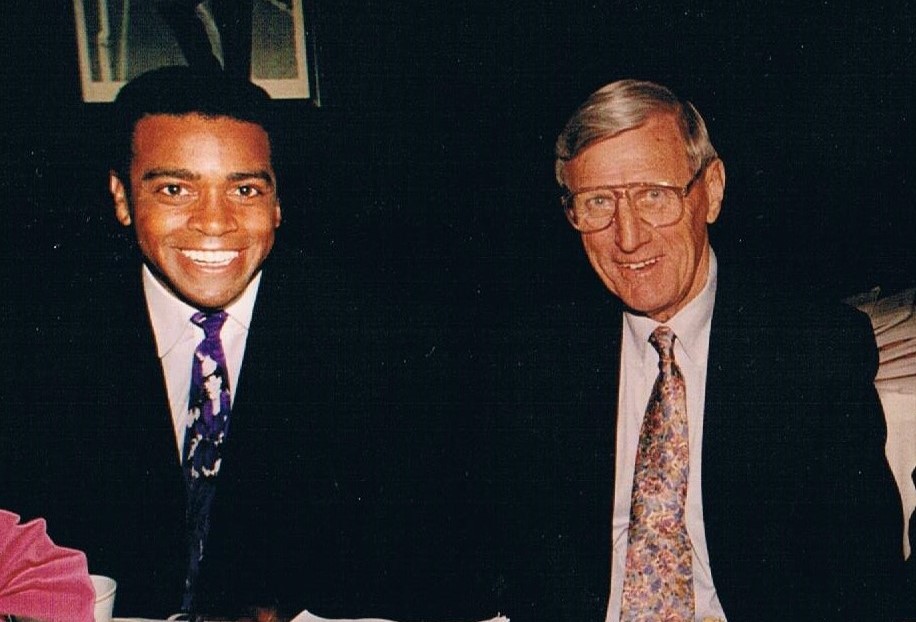

In the past week, broadcaster and former NFL wide receiver Ahmad Rashad appeared on Bomani Jones’ ESPN podcast, “The Right Time.”

Ahmad was at the University of Oregon, on one of the nation’s most volatile campuses, during a different turbulent time. He was a slotback and running back for the Ducks for three seasons, from 1969-71.

He told Jones: “We had a coach that was really interested in developing young men.”

Rashad alluded to protests against the Vietnam War and against Dow Chemical, which supplied napalm to the U.S. military and sent corporate recruiters to campuses.

“Our coach let us miss practice to go to these demonstrations,” Rashad said. “To be real human beings. . . (He) took real care to understand the most important thing is to know how to get along with other people and do that. . . His thing was to make sure that everybody sort of got a chance to ask questions. To say why.”

That coach was my father.

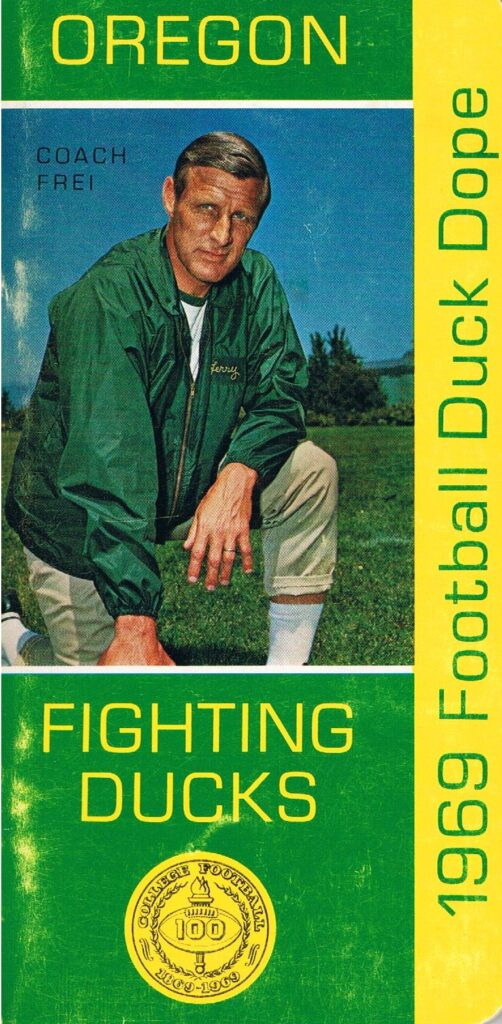

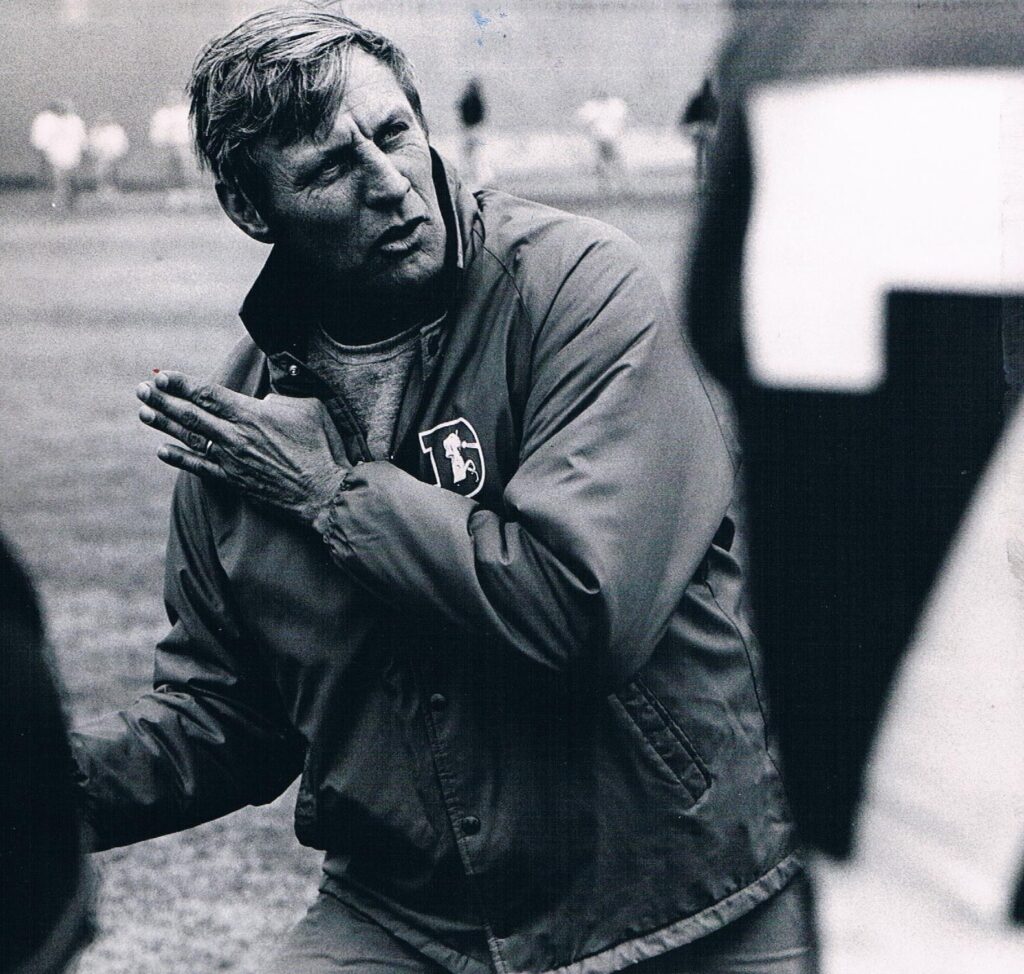

Jerry Frei.

I wish I could say this in person.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad.

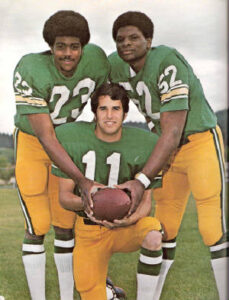

Ahmad, a terrific all-around athlete known as Bobby Moore in college, also played on both the freshman football and basketball squads in the era when freshmen still were ineligible for varsity competition.

In December 1968, the night before the freshman basketball season opener against Clark College in Vancouver, Wash., the young and earnest freshman team coach told Ahmad and another football scholarship player, Bill Drake, to get haircuts before the bus trip, trimming back their “Afro” styles.

Some, perhaps unfairly, considered the coach’s edict a backhanded swipe at the football program. Regardless, my father was unhappy. So were Black Student Union leaders. The university’s beleaguered acting president, Dr. Charles Johnson, called an emergency meeting of the Faculty Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics to consider the matter and essentially made it a public session, leaving it open for student leaders to attend.

After volatile discussion, Johnson issued a statement saying, “Hairstyle should not be a condition of participation on athletic teams at the University of Oregon.” Rashad and Drake made the trip to Vancouver. The freshman team coach didn’t.

None of this sat well with many Oregonians, either. My father supported Johnson’s statement and his football players.

With the Civil Rights Act only a few years in the rear-view mirror and with the nation in turmoil, hairstyle was a major issue in the debate over the right to freedom of expression. Many coaches and administrators considered discipline to be linked to hair length and facial hair. If you had long hair, if you dared to grow facial hair, you were “undisciplined.” Especially if you happened to be African-American.

Ahmad Rashad, Dan Fouts, Tom Graham

Later, my dad downplayed his stand about hair, saying he mainly didn’t get why so many considered it a big deal. To him, it wasn’t. There was so much more to worry about, different ways to define discipline. (Really, as I type it now, it seems almost silly that hair was such a front-burner issue. Believe me; it was.)

He was an unlikely candidate for progressivism on one of the nation’s most cauldron campuses. It was fitting that instead of a conventional marching band, Oregon for a time had a 12-man rock band in the stands at the games, looking as if they could be next up on stage at Woodstock.

The coach’s roots were as a Wisconsin farm boy.

His sophomore season as a Wisconsin Badgers guard was in 1942.

His junior season was in 1946.

His later Oregon and NFL press guide coaching bios didn’t explain the gap.

It was as if he had been off fishing.

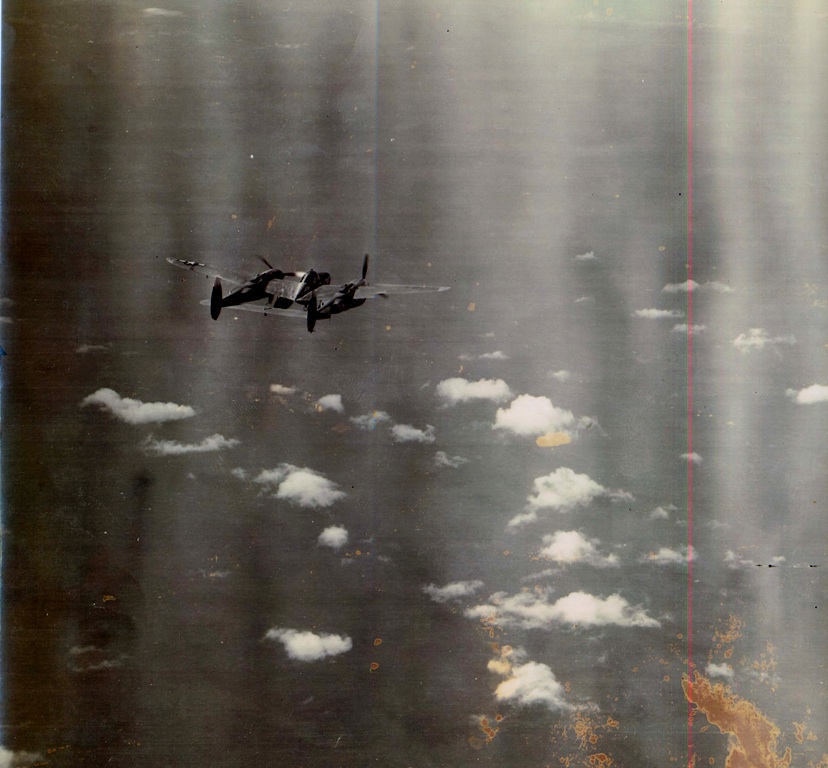

The fact was, he was an Army Air Forces Lockheed P-38 fighter pilot in the Pacific Theater, entering the service at 18 and flying the first of his 67 missions in the one-man, twin engine plane in 1944.

He had just turned 20.

His planes’ guns had been replaced by cameras. The job: Fly in alone, or with one other plane, over enemy targets to take photos in advance of the bombing runs. He later joked it wasn’t accurate to say he was unarmed. He had a pistol in a shoulder holster.

His one self-homage to his fighter pilot service was that when he succeeded his mentor, the great Len Casanova, he asked that his Oregon teams go by “Fighting Ducks” — without publicly explaining why. The original artistic mockup of the toughened-up Fighting Duck mascot is in my sister’s house and the nickname variation appears in the football and basketball jersey rotations.

After what he had been through at their ages, he resolutely refused to call his players “kids,” though many, not understanding the reasoning, mocked it. To him, they were “young men” or “young people.” (He still wouldn’t go along with today’s coaches almost universally using “kids.”) It was more than hair: As Rashad noted, he didn’t try to limit his players’ expression away from the field, whether about the war or anything else. Although he had future NFL players, including Rashad, Drake, Tom Blanchard, Bob Newland, Dan Fouts, Tom Graham, Tom Drougas, and Leland Glass, I’m also proud of hearing from his former players who cited him as an influence in whatever they did after leaving the campus.

That included after the concussion and CTE issue came to the forefront — I’ve written many stories about it myself — and former Ducks Don Stone and Steve Bailey told the Eugene Register-Guard’s Austin Meek how my father reacted to their concussions and other issues. “I played for a man who was well ahead of his time as far as handling those sorts of things,” Stone said.

My father didn’t tell them that he had severe headaches during his senior season at Wisconsin. After he played in the first two games, the Madison papers charted the chances of him being able to get on the field each week and ultimately reported at midseason that doctors had suggested he stop trying to return.

“Giving up football was hard to take, but Jerry realized that it was the only thing to do,” wrote the Wisconsin State Journal‘s Henry J. McCormick. His issue was labeled “an acute sinus infection.” In actuality, he suffered repeated concussions. It was another reason he was especially conscious of the issue with his players when he moved into coaching.

In 1970, the Ducks beat USC, UCLA and then-powerful Air Force, and finished tied for second in the Pacific 8 Conference. Jerry Frei twice was named UPI’s national coach of the week. The next season, the Ducks weren’t helped by early-season paycheck non-conference road games at Texas and Nebraska, and eventually closed out with a bitter 30-29 loss to rival Oregon State.

I heard senior Ducks linebacker Tom Graham grab the microphone on the field during senior-day ceremonies and declare: “I’m going to be a Duck until I die.”

I was a South Eugene High junior.

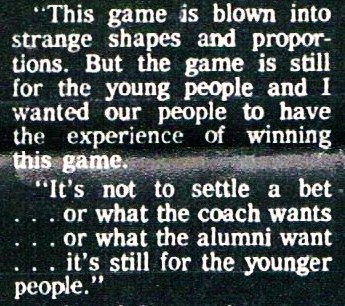

I made my way into the cramped coaches’ dressing room at Autzen Stadium. What my father told the writers is preserved in this snippet from Neil Andersen’s story in The Oregonian:

I never was more proud of him.

Two months after that loss to OSU, long after all seemed settled, Jerry Frei suddenly resigned in late January 1972. Some boosters, mostly in Portland, had lobbied for him to “instill discipline” and also be told to fire assistant coaches, in part to give them a feeling of power to influence change. (Some things never change.) He always believed they were going after him and that they knew he wouldn’t do it.

His 1971 staff included John Robinson, George Seifert, Bruce Snyder, John Marshall, Ron Stratten and graduate assistant Gunther Cunningham.

Who?

Seifert won two Super Bowls as head coach of the 49ers. Robinson won a national championship as head coach at USC and got to the NFC championship game as head coach of the Rams, losing to … Seifert’s 49ers. Snyder was an accomplished collegiate head coach at Utah State, California and Arizona, arguably coming within one Rose Bowl play of winning a national championship with Jake Plummer and the Sun Devils. Marshall was a long-time NFL defensive coordinator. Cunningham was the popular head coach of the Chiefs in addition to being perhaps the top defensive coordinator in the league for many years. Stratten became an NCAA executive and then a successful businessman.

That’s getting ahead of the story.

Iain Moore, the radical student body president, issued a lengthy statement of support. A snippet: “Jerry Frei’s resignation supports the thesis that I have consistently advanced, that the structure of athletics in the United States is such that it subverts what should be the goals of the program. . . In an un-ideal situation, Jerry Frei ran as ideal a program as possible with the broad interests of the participants pre-eminent in his mind and actions.”

(Eventually, my 2009 roman a clef novel, The Witch’s Season, was the thinly veiled story of that campus, that team, and those times.)

After he moved on to the NFL, he spent most of his 30-year career as an offensive line coach, scout and administrator — including as the director of college scouting — with the Denver Broncos.

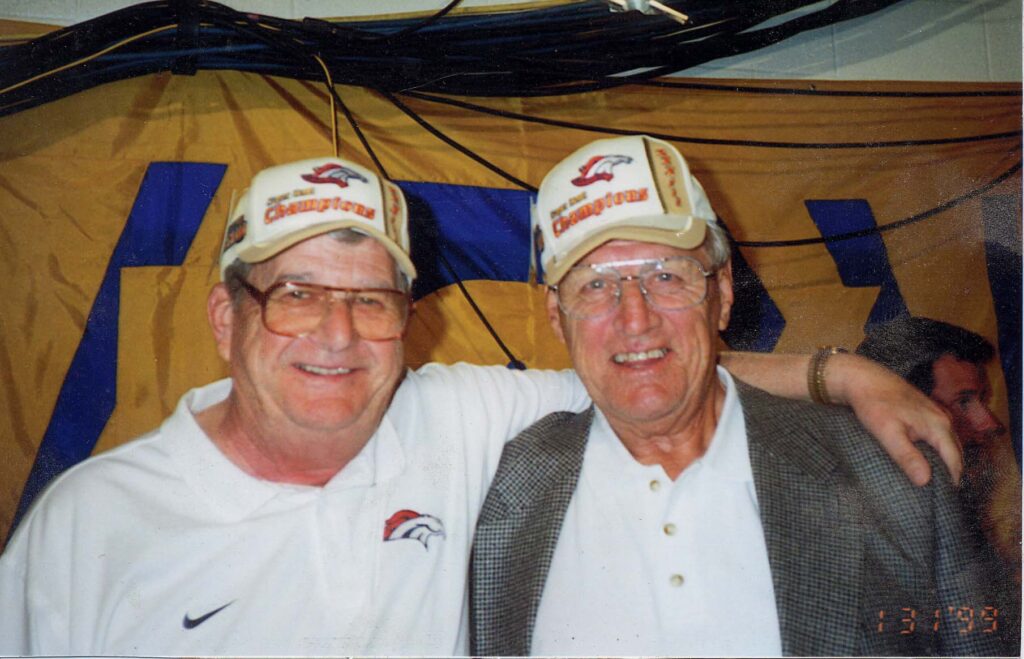

He enjoyed the work, eventually sharing an office as he was winding down with another former Pac 8/10 head coach — his close friend, Jack Elway, the Broncos’ director of pro scouting.

As time went on, we belatedly showed more appreciation for those who served in World War II. I had known the broad outline, but in 2000, I finally sat down with him and “interviewed” him about his service for a Veterans Day column — and for posterity.

“I think all of us didn’t feel like were being different,” he told me. “Or that we were doing anything spectacular. Everybody did it. It wasn’t, ‘Look at me, I’m a soldier.’ I don’t think anyone was concerned about memorials or anything like that. I think everyone was looking at it like, “I did what I had to do.’ Everyone who survived gave a big sigh of relief, and felt sad for those who didn’t.”

He still was a scouting consultant and had a scouting report on Michigan tackle Jeff Backus on his laptop screen at home when he suffered fatal cardiac arrest at age 76 in 2001.

Fouts’ immediate comment to the Denver Post’s Patrick Saunders was, “Jerry was more than a coach. He was a friend and a man I could look up to. At that time, Oregon was kind of an off-Broadway version of Cal-Berkeley. Things got pretty crazy on campus. But he was always so non-judgmental. He was willing to treat us all as individual, mature young men.”

Tom Graham officiated at my father’s memorial service in Denver. He had a productive NFL career, starting with the Broncos. He and his wife, Marilyn, kept their home after he was traded they stayed rooted in Denver. Their son, Daniel, was an All-American at Colorado and also played for the Patriots, Broncos, Titans and Saints.

Graham told the story of how I called him to break the news, saying, “Tom, Dad just died.”

Tom told the crowd, “He didn’t say, ‘My dad.’ He said ‘Dad.’ And I felt like my dad died.”

In the pass-around the microphone period that followed, Fouts told a story about that last Oregon State game.

He said that with Oregon hoping to drive for a game-winning field goal, but still out of range, he turned the wrong way to make a fourth-and-short handoff and came off the field in tears. He said (incorrectly) that he had lost the game. He told those at the memorial that my dad immediately and decisively, with everything else going on, gave him a pep talk and told him to keep his head up. Fouts several years earlier had organized a tribute dinner for my father in Eugene, saying he wanted the players to tell him what he meant to them before it was too late.

Seifert, then the Panthers’ head coach, had traveled to Denver and delivered a touching tribute.

Pat Bowlen and Mike Shanahan spoke up, too. Jack Elway told of their friendship and noted how their corner suite in the University of Northern Colorado dormitory during training camp was the Happy Hour gathering spot. Jack joked that the next morning, he’d ask Jerry to whom he needed to apologize — and my dad always had a list.

Rashad sent me a long email of condolence and support, and I read it at the service.

My father had been a high school coach in Portland before serving as a Casanova assistant for 12 years. In Portland in 1989, I attended a 40th reunion of Grant High School’s 1949 state championship team with him. While at Grant, he was a young assistant fresh out of college in his first job, working under Ted Ogdahl, who had earned the Silver Star in Pacific fighting. My dad wasn’t much older than those Grant Generals, including NFL quarterback George Shaw, their star, but I could tell what he and Ogdahl had meant to them.

After moving to the NFL, he missed high school and college football and his deeper personal involvement with the players. I also know if he had remained a college head coach, he eventually would have had to step back or it would have eaten him up. He couldn’t be the imperial, dictatorial authoritarian type.

He did have valued relationships with some of his NFL players as a line coach, including with Bobby Maples, Mike Current and Claudie Minor, and after his stint with the Bears, always considered Walter Payton the best football player ever to set foot on the planet.

But it was different.

Eventually, in a Broncos’ senior adviser role, he was a voice of support for younger players finding their way. That was when it was almost as if he was back at Oregon.

When Tom Graham died of brain cancer in 2017, I was an honorary pallbearer.

I considered myself to be representing my father.

Tom indeed was a Duck until the day he died.

He still is.

Ahmad Rashad spoke up again about his college coach again last week.

Happy Father’s Day.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming; Third Down and a War to Go; and ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.

More from The Woody Paige Sports Network:

- Woody Paige: 52 years later, America is still fighting the same fight

- What if the Trail Blazers took Michael Jordan in the 1984 NBA Draft?

- Betting odds to lead the NFL in rushing yards in 2020

- Woody Paige: Thanks to MLB owners, there will be crying in baseball

- Stick to Sports? No thanks. We need more athletes in politics