Three of the first five choices in the 2019 NBA draft were coming off their freshman collegiate years and will be rookies when the 2019-20 season opens Tuesday.

Duke’s Zion Williamson (No. 1) is with the Pelicans, although his NBA debut will be postponed by a right knee injury. Duke’s RJ Barrett (No. 3) is with the Knicks, and Vanderbilt’s Darius Garland (No. 5) is with the Cavaliers.

They declared for the draft after their freshman seasons and were done with the college game.

The only non-freshmen in the top five (both were sophomores) were Murray State’s Ja Morant (No. 2), who is with the Grizzlies, and De’Andre Hunter (No. 4) of Virginia, who is with the Hawks.

The one-and-done system annually triggers hand-wringing, but we’re accustomed to it.

Hockey’s a bit different. And a bit more complicated. Plus, much more sensible.

The NBA would be smart to take notes.

The 2019-20 NHL season opened October 2, and of the top five 2019 draft picks, only the top two are currently playing in the the league.

Jack Hughes (No. 1), from the Michigan-based National Team Development Program, is with the Devils. Finland’s Kaapo Kakko (No. 2) is with the Rangers. No. 3 Kirby Dach of major junior’s Saskatoon Blades, drafted by the Blackhawks, is on a rehab assignment with Rockford of the American Hockey League and is expected to join the the NHL team soon.

Bowen Byram, who went fourth to the Avalanche, is back with major junior’s Vancouver Giants for another year of seasoning. That was expected. And Alex Turcotte, who went at No. 5 to Los Angeles, is a freshman at the University of Wisconsin – with the Kings’ blessing.

The bottom line is that the NHL’s draft-and-watch system, with initial draft eligibility at 17 or 18 (depending on where their birthdays fall), is better than the NBA system. Hockey players don’t have to opt in, as is necessary in the NBA. They’re in the pool in their draft year.

Only the most elite – perhaps only the top three picks — go straight from being drafted to the NHL. The rest remain under draft-and-watch scrutiny, whether they’re in major junior, NCAA hockey or Europe.

The NBA, which requires draft picks to be of an age that would take them through one year of college, would be wise to mimic the NHL system.

Imagine watching college hoops, already knowing which NBA team the top players already have been drafted by and are destined to play for. Someday, and it might even be right after their teams have been eliminated from postseason play. (In hockey, UMass sophomore defenseman Cale Makar — the winner of the Hobey Baker Award as NCAA hockey’s top player — within 48 hours last April went from playing in the Frozen Four championship game to making his NHL debut with the Avalanche in the first round of the playoffs against his hometown Flames.)

In basketball, that would add to the fun, even after your bracket is shot and your upset choice of St. Bonaventure didn’t work out.

NCAA basketball’s defenders correctly point out that one-and-done happens in NCAA hockey, too, and it is curious that so few seem to care or consider that additional evidence that “student-athlete is an oxymoron.”

It’s belittled in basketball; it’s accepted in hockey.

But the NHL system’s additional caveats, mainly involving teams drafting and holding on to the players’ draft rights for a few years (it varies, depending on the circumstances), add legitimacy and are based in common sense.

It’s routine for NHL picks to be committed to NCAA programs when they’re drafted. NHL teams not only know it, they’re fine with it.

Players who end up in college hockey for at least a year deliberately have avoided major junior, which the NCAA considers toxic to eligibility because of the stipend-type payments involved. (I won’t even begin to get into the hypocrisy involved there.)

Major junior, played in three leagues under the Canadian Hockey League umbrella, still is the top North American feeder to pro hockey, but NCAA hockey is a close second.

In light of the NCAA’s apparent horror when basketball players prematurely deal with agents, it’s hilarious to note that already-drafted NCAA hockey standouts have “advisors” – and, in an amazing coincidence, those “advisors” happen to be agents.

While prospects are playing in college, schools openly and proudly list which NHL teams have drafted their players. NHL executives and scouts are in the press box and outside the locker room after the games, checking on and touching base with draft choices.

In the NBA, recent high school graduates – who are the same age as NHL draft picks – are unable to enter the draft. One one year of college ball (or the equivalent wait) is required.

Granted, evaluating phenoms playing against Brooklyn’s Buchanan High is riskier than scouting them against Villanova.

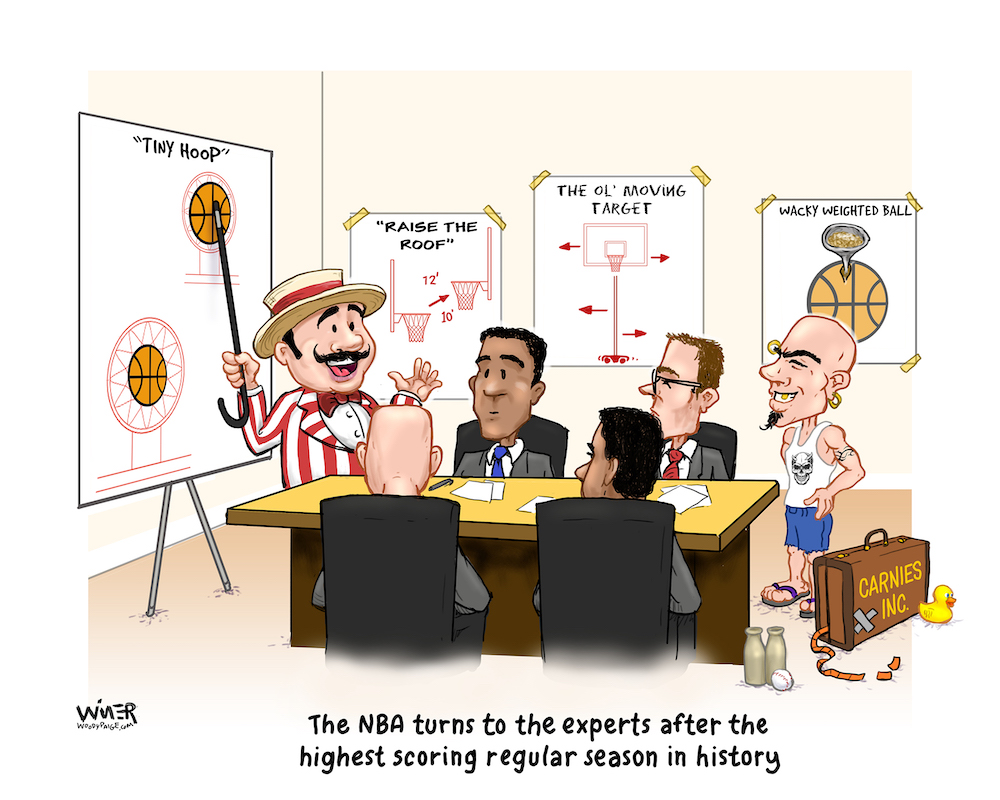

Here’s how to get the best of both worlds. Emulate the NHL system and make the initial universal NBA draft age 18 while adding rounds, if and when it is feasible under the league’s rules and collective bargaining agreement. The most savvy organizations would thrive in this scouting challenge.

Even more so than now, you’re projecting. Some will say it’s unseemly that the NBA is getting involved in the high school game? Too bad. Part of the fun in the NHL is when players are drafted late at age 18 and blossom in college or major junior, and the teams are as surprised as anyone.

One catch: Under relatively recent changes, if drafted players stick in college for a full four-season career, they can become unrestricted free agents on August 15, increasing the pressure for NHL teams to sign choices they’re still high on after their junior years — or at least in the four-month window after their senior seasons, when the problem is that players have incentive to wait and see what other teams might be interested.)

Absolutely, the most elite hoops stars would turn pro on the spot and never play a second of college ball.

That’s none and done.

And there’s nothing wrong with it, in any endeavor. It works in hockey. If you’re ready to make a living, fine. Whether you’re a painter, singer, writer, actor, or a basketball player.

In basketball, it’s a better system than we have now.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming, Third Down and a War to Go, and ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.