The campaign has picked up steam.

No, not that one.

The one that goes: “Pay college athletes!” “They bring in the revenue.” “Mountains of revenue.” “It’s only right!”

Why is this so hard to grasp and is so often dismissed with a wave of the hand by the proponents of “paying” college athletes?

We already do pay college athletes in the marquee sports.

We have done so for many decades. The increase in the worth of those payments has far outstripped the rate of inflation.

It is called … “a scholarship.”

A free ride.

A bill for $0.00.

Ask young professionals drowning in student debt years after graduating.

Ask parents trying to put kids through college in 2019.

Ask students holding down three part-time jobs and trying to pay their own way or lessen the amount of debt they take on. Perhaps some of them receive limited scholarship aid, based on merit and/or need, but a full ride usually is a fantasy.

Ask them if a full athletic scholarship, or essentially a free college education, should be waved off as insignificant.

Yet, that’s the way many seem to be portraying the plight of “exploited” athletes when raising the issue of paying players — especially in football and men’s basketball.

This has come up again because of the passed California legislation that, if signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom, or it becomes law without his signature, would allow athletes at the state’s NCAA schools to receive payment for the use of their names, images and likenesses.

The money would not come from the schools, but they’d be part of monitoring the process.

Senate Bill 206 unanimously was approved by the California Assembly on Monday and by the Senate on Wednesday. It would not go into effect until Jan. 1, 2023, and it would prevent the NCAA from banning schools from competition because of ancillary pay to athletes.

NCAA President Mark Emmert and 21 others responded with a letter to Newsom that said, in part:

“If the bill becomes law and California’s 58 NCAA schools are compelled to allow an unrestricted name, image and likeness scheme, it would erase the critical distinction between college and professional athletics and, because it gives those schools an unfair recruiting advantage, would result in them eventually being unable to compete in NCAA competitions.”

So it would be additional money in theory coming from outside the traditional system, yet it’s still being portrayed as about time, because paying college athletes was long overdue.

(I say “in theory” because payments imaginatively delivered to some elite athletes go back to the days of leather helmets and high-top Chuck Taylor All-Stars.)

That implies that athletes aren’t paid now.

They are.

The value, of course, varies depending on the cost and nature of the school, mainly if it’s public or private.

Regardless, college athletes on full scholarships receive significant compensation.

Can’t we at least start with that as the foundation for the discussion?

Plus, it’s as if the “cost of attendance” supplemental payments (i.e., stipends) to scholarship athletes approved in 2015 don’t exist at all.

The puzzling thing is that when athletes themselves disdainfully dismiss that scholarship’s worth and a free education as insignificant, they’re selling themselves short.

They’re buying into the “student-athlete is an oxymoron” stereotype – even if it doesn’t fit. (And it usually doesn’t.)

So it all needs to start with that concession. Allowing elite players – and that’s what it would be, the elite, not nearly as democratic as virtually roster-wide scholarships in football and basketball – to profit from use of their likeness and name sounds so fair and simple in theory.

One such athlete who would have profited tremendously from the proposed bill is former Florida quarterback and 2007 Heisman Trophy winner Tim Tebow.

Tebow recently joined ESPN’s First Take and passionately spoke out against the idea of paying college athletes.

“It changes what’s special about college football and we turn it into the NFL where who has the most money that’s where you go,” said Tebow. “That’s why people are more passionate about college sports than they are about the NFL. That’s why the stadiums are bigger in college than the NFL because it’s about your team, about your university, about where my family wanted to go, about where my grandfather had a dream of seeing Florida win an SEC championship and you’re taking that away so young kids can earn a dollar. And that’s not where I feel like college football needs to go.”

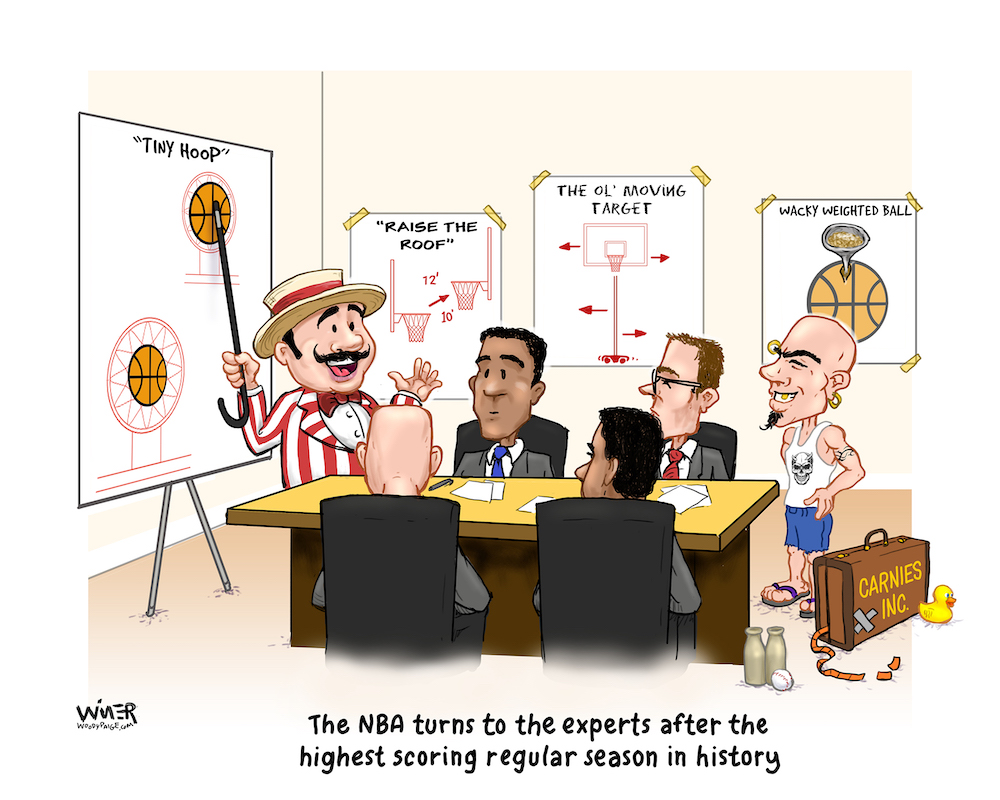

I admit I haven’t read the legislation. But I know enough to know it’s also a Pandora’s Box and that defining and regulating what is permissible and what isn’t will be a nightmare. That is, unless we just throw up our hards and say anything goes? If you can get it, you’ve earned it.

It would be all on merit? The marketplace rules? OK. Are you allowed to tell a five-star prospect during recruiting that he or she is guaranteed $125,000 a year in ancillary income, whether (allegedly) for autographs or for signing memorabilia? (Or even if you’re not allowed to offer such guarantees, do it anyway?) At what point is it good, old-fashioned bidding? The monitoring would prevent that?

Dream on.

Go back to the world of football stars’ “jobs” being paid to be on call to shovel snow from the automobile dealer’s lot – in the summer? Or working for an airline, being required to show up several minutes per week and be able to get free plane tickets for family, leading to a roster including many out-of-state players from the airlines’ “hub” cities?

This is not a reflexive backing of the NCAA, which tends to portray any innovation or concession to marketplace conditions as potential for disaster. But even then, the tendency to portray it as some sort of evil junta imposing its will ignores the fact that is a member organization. It also overlooks the fact that the thick rulebook and seemingly overdone rules in many cases are responses to past excesses and evidence that the cheaters will find ways to get around anything that doesn’t painstakingly spell out the rules.

I’m not as much against the concept of the California legislation as I’m flabbergasted when proponents of such measures act as if a four-year ride to Stanford or Generic State U. or Wisconsin or Vanderbilt or Clemson or anywhere else isn’t even part of the picture.

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming, Third Down and a War to Go, and ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive is here.

Amen, and let’s keep in mind that an athletic scholarship in a revenue-generating sport is typically a five-year ride, not four. Here in Michigan, that means $125,000 in value for an in-state student and more than $200,000 for a non-Michigander. At Stanford or Duke, it’s $300,000.

One of the things the NCAA attempts to do is keep playing fields level. Clearly, it doesn’t always succeed. But that’s why there’s an 85-scholarship limit in Division I football — so that Alabama and Oklahoma can’t swallow 120 players when most programs lose money and can’t afford what they already have. Allowing players to be paid would only widen the gap.

NCAA regulations regarding player compensation exist only because universities and boosters have a long and proud history of cheating. Easing restrictions will make the problem markedly worse.