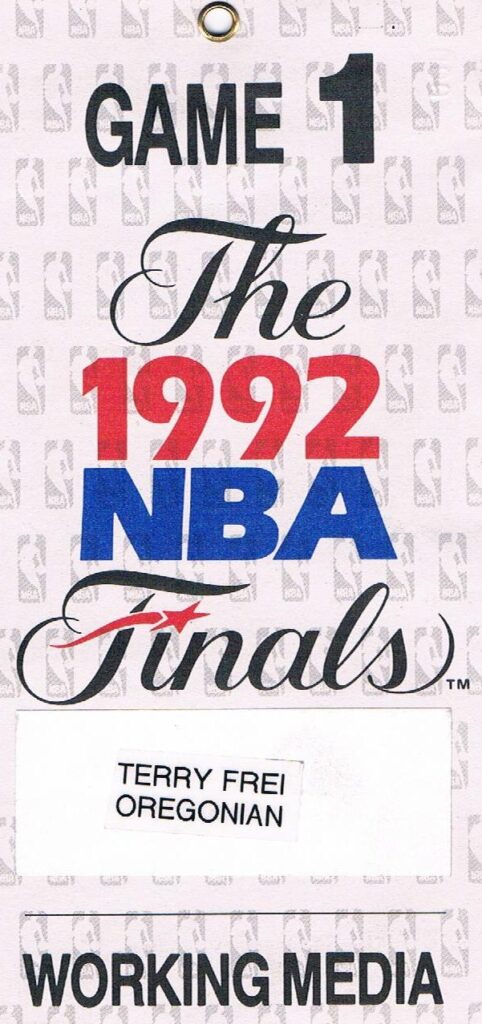

In my live Portland Oregonian column from the series-concluding Game 6 of the 1992 NBA Finals in the Chicago Stadium, I noted:

“In the next few days, in the aftermath of the Bulls’ second straight championship, somebody’s probably going to try to pawn off a piece on the ‘Building of a Two-Time Champion.’ It would list all these brilliant decisions made by the Chicago front office over the years. Drafting Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant. Trading for Bill Cartwright (in a rotten exchange for Charles Oakley). Getting John Paxson. But, really, once the Bulls drafted [Michael] Jordan, and discovered just how lucky they had been, the rest was about as tough as deciding whether it should be pepperoni or sausage on the Domino’s. Jordan can make obvious decisions seem inspired.

The Bulls were brilliant only if somebody slipped decision-clinching negative information into the Blazers’ scouting file on Jordan, and/or tampered with [Sam] Bowie’s college-days X-rays. The challenge after drafting Jordan was: Just get him a decent supporting cast, to steal a phrase. That probably could have been done with the NBA Central Scouting reports and a satellite dish in somebody’s back yard. They already had the man that would revitalize the game in Chicago. For that, they had — and still have — Portland to thank.”

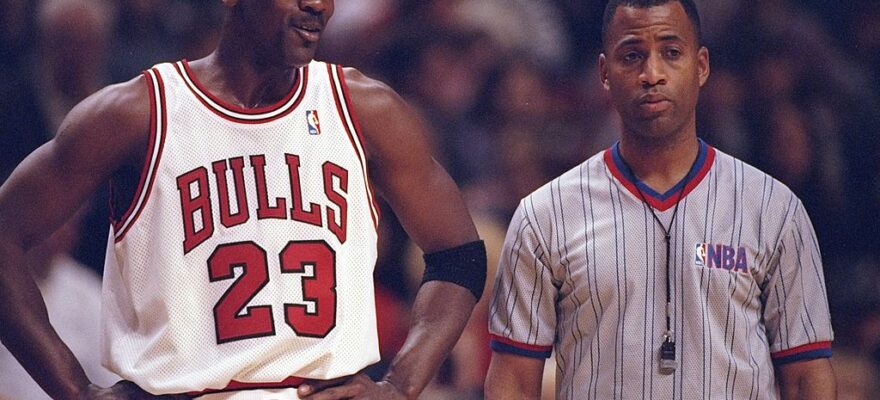

In fact, during the celebration, Jordan several times — both on the floor and the public-address system and later — thanked the Bulls for drafting him.

Implicitly, he also was thanking the Trail Blazers for not taking him.

Amid the current fascination with ESPN’s terrific “The Last Dance,” I wondered:

What if . . .

In an alternative universe, what if it went this way?

***

At Madison Square Garden’s Felt Forum on June 19, 1984, NBA commissioner David Stern was a bit nervous.

This was the first NBA draft since he moved up from executive vice president four months earlier, to take over for retiring commissioner Larry O’Brien.

Arriving at the podium, Stern jokingly pulled the microphone down about a foot and wryly noted: “Larry was a bit taller…”

After his welcoming remarks, Stern announced that the Houston Rockets, who won the coin flip for the top overall pick, selected University of Houston center Hakeem Olajuwon.

The Portland Trail Blazers, who acquired the pick from the Indiana Pacers, were next up.

Returning to the microphone, Stern intoned: “With the second pick of the 1984 NBA draft, the Portland Trail Blazers select Michael Jordan from the University of North Carolina.”

After that, the Bulls took Charles Barkley of Auburn third, the Mavericks took Sam Perkins of North Carolina fourth, and the 76ers claimed Kentucky center Sam Bowie fifth.

Bowie had mixed feelings, since it seemed that at one he was destined to go to Portland at No. 2 and had slipped three spots. Yet he was born and raised in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, 112 miles from Philadelphia, and it set up a homecoming.

The Blazers had played coy up to the draft, since they had nothing to lose by seeing what trade offers might come for the No. 2 pick. However, their actions showed they realized that on paper, they needed a center more than another shooting guard/small forward.

Before the May 23 coin flip determined the Rockets would draft first and the Blazers second, Stern fined the Blazers $250,000, saying a meeting with Olajuwon and “friends,” plus a meeting with Georgetown center Patrick Ewing and his coach, John Thompson, had violated tampering rules.

Although rumors spread that the Blazers and Olajuwon had agreed to a contingency contract, Stern said that wasn’t true and agreed the Blazers mainly had explained the NBA salary cap, a new phenomenon at the time. Ewing decided to stay another year at Georgetown.

After losing the coin flip, Portland GM Stu Inman said a major consideration would be the team’s physical exam of Bowie, the tremendously athletic 7-foot-1 center who had been a high school phenom and was selected to the 1980 Olympic team — the one that didn’t go to Moscow because of the U.S. boycott — after his freshman year.

Bowie sat out two seasons after his sophomore year because of an initially misdiagnosed stress fracture before returning for one more season — a season that seemed to indicate Bowie had recovered.

Both on draft night and over the next few days, Inman patiently explained the reasoning for passing on Bowie. The debate had raged pre-draft; and it continued. Inman parried challenges from cynical writers and broadcasters that Jordan, unquestionably talented, didn’t augment the Blazers’ roster nearly as much as a big man would have. At North Carolina under Dean Smith, he had been more of a standout on a talented team– most notably hitting the game-winning shot against Georgetown in the Final Four championship game as a freshman — than a phenom.

The Blazers hadn’t had an elite true center since Bill Walton, and 6-foot-10 Mychal Thompson was more of a power forward. Wayne Cooper was a terrific backup. But he was a backup.

Most importantly, the Blazers already had Clyde Drexler, drafted the year before, and Jim Paxson at shooting guard. Coach Jack Ramsay — Dr. Jack — already was wrestling with juggling their minutes and how much to have them on the floor at the same time, with one at least nominally at small forward. Drexler played only 18 minutes a game as a rookie and Paxson was the Blazers’ acknowledged leader and star.

Essentially, it boiled down to this: If Bowie’s health and resilience had been assured — or at least as much as was possible in the world of sports — Portland would have taken him. An athletic big man who can both play inside and shoot capably from the outside? Who wouldn’t want that? (The Rockets did. And it was clear the Blazers would have taken Olajuwon if they won the coin flip.)

The Blazers, though, were diplomatic. They couldn’t come out and voice too much skepticism about Bowie’s physical status without coming off as jerks, so they simply say weighed all factors, including what they gleaned from the seven-hour physical, and decided the tantalizing Jordan was the right choice as the best player available. The teams immediately behind the Blazers took note. If the Blazers, who had more need of a center, cringed at Bowie’s physical, shouldn’t they?

So the Portland post-draft mantra was: You build a roster of the best players you can get and worry about the rest later.

This was often overlooked: During the process, the Blazers considered acquiring the high-scoring forward Kiki Vandeweghe from Denver. But as the choice of Jordan crystallized, Portland backed away from that. At one point, the Blazers had an offer on the table of forward Calvin Natt and Cooper, and they considered sweetening it with guard Fat Lever.

But they eventually decided to take Jordan and also not to trade out of the No. 2 pick.

So after the 1984 draft, the Blazers core looked like this:

Center — Cooper, Thompson, Audie Norris.

Forward — Kenny Carr, Natt, Jerome Kersey (Portland’s second-round pick).

Guard — Darnell Valentine, Lever, Eddie Jordan, Paxson, Drexler, Michael Jordan.

Dr. Jack had his challenges ahead of him and he butted heads with his stars, but always had their respect. He also was open-minded enough to not worry about position labels, joking that during his playing days in the peach basket era, there were just guards, forwards and a center. Period. Turning serious, he said he always had been adaptive as a coach, and he would continue to be.

Eventually, amid other moves in the evolution of the roster, as Jordan’s greatness became even more obvious, the Blazers traded Paxson to the Celtics. Jordan and Drexler had their moments of discord, but for the most part co-existed on the floor — and won.

All along, the Blazers were an unconventional mix, but it worked.

They took over from the Lakers as the perennial Western Conference power and won nine NBA titles in a span of 15 seasons.

Ramsay stayed with the Blazers through the 1989-90 season, retiring at 65 and handing the reins over to long-time assistant Rick Adelman.

With both Jordan and Drexler on the 1992 Olympic Dream Team, the Blazers drew even more international attention. Arvydas Sabonis, the second of the Blazers’ two 1986 first-round picks had rehabbed his Achilles’ injury in Portland before playing for the Soviet Union’s gold medalists in Seoul, also was in Barcelona. This time, he played for Lithuania in the wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Intrigued, the much-injured center joined Portland for the 1992-93 season, rejecting a huge three-year contract offer from Real Madrid.

He wasn’t the Sabonis of the mid-80s before his injury problems struck, but still was more of an elite NBA center than he would have been had he waited until, say, 1995.

Drexler retired after the 1997-98 season, Jordan the next year.

Jordan was 35 and while he joked about his fascination with baseball, he never followed up on his threat to give it a try. His closest friend in the game actually was NBC broadcaster Ahmad Rashad, and that seemed a natural given that Rashad — as Bobby Moore — had starred in football down Interstate 5 at the University of Oregon, where Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman got an underdog shoe company started.

There were some side dramas, including the friendly shoe endorsement rivalries, with Jordan representing Nike, by then based in the Portland suburb of Beaverton. There, Nike constructed a glitzy World Campus as its headquarters.

Drexler first endorsed and wore KangaRoos, then switched to Avia, which started out in Beaverton, too, before being sold to Reebok.

But the Blazers were a dynasty. Every once in a while, pundits mused what might have happened if the Blazers had drafted Sam Bowie, not Michael Jordan, in 1984. To be fair, Bowie proved the doubters about his physical resiliency wrong, suffering nothing more than routine, minor injuries in his long and productive career with the 76ers and Lakers.

But he wasn’t Michael Jordan.

In 2020, ESPN unveiled a 10-part series about the Blazers’ Glory Years with Jordan in the starring role.

It was called: “Don’t Try to Pump Your Own Gas.”

About Terry: Terry Frei is the author of seven books. His novels are Olympic Affair and The Witch’s Season, and among his five non-fiction works are Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming; Third Down and a War to Go; and ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age. Information is available on his web site, terryfrei.com. His woodypaige.com archive can be found here.

More from The Woody Paige Sports Network:

- Woody Paige: ‘Michael and me’; detailing my friendship with Michael Jordan (Part 1)

- Woody Paige: That time I played blackjack with Michael Jordan in Monte Carlo

- It’s time for the final buzzer to sound on 2019-20 NBA, NHL seasons

- Jalen Green, NBA development and the benefits to college basketball

- Betting odds to win 2020 NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year

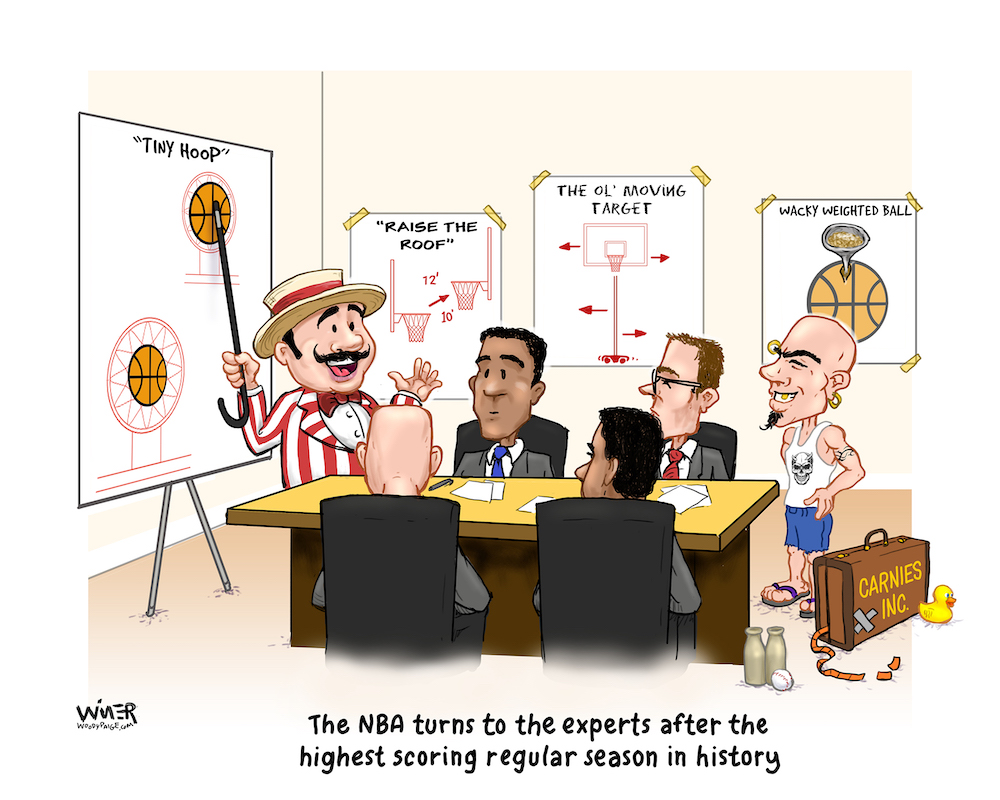

- Don Shula: A Dolphin into the Great Beyond (CARTOON)